Another victim for the 'Graveyard of Empires'?

By Geoffrey Murray

China.org.cn, December 5, 2011

The British tried three times between 1839 and 1919 to subjugate Afghanistan and failed each time as the country lived up to its historical reputation as a 'graveyard of empires'. Now, we may be chalking up defeat number four (this time in alliance with countries like the United States and Australia).

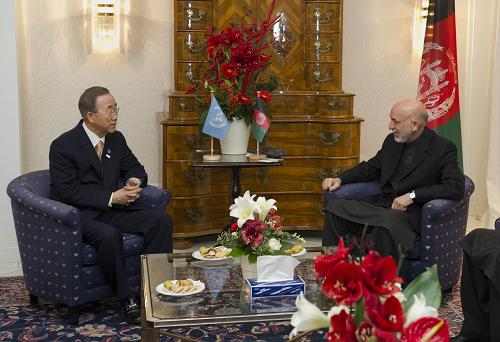

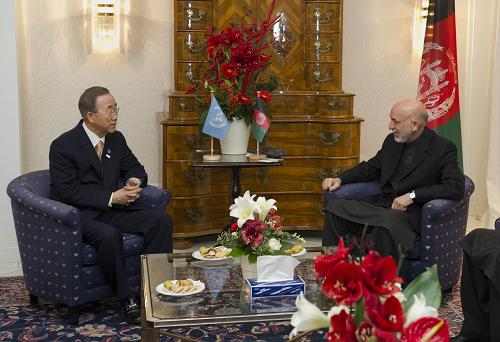

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (L) meeting with Afghan President Hamid Karzai in Bonn on December 4, 2011, ahead of a major international conference on the war-torn country. The Bonn conference on December 5 will discuss Afghanistan future beyond 2014, when NATO-led international combat troops will leave, and comes ten years after a previous landmark meeting on Afghanistan in the German city. [Xinhua/AFP]

In the German city of Bonn this week a conference is being held to try and chart a path forward towards stabilizing the country at a time when foreign troops are preparing to head home from a decade-long war against the radical Islamic Taliban movement that seems increasingly unwinnable.

The prospects in Bonn do not look good. For a start, we have a situation where perhaps the single most important player, Pakistan, will not be there, having decided to boycott the meeting to express its anger after NATO aircraft killed 24 of its soldiers in a cross-border attack the alliance has called a 'tragic accident'.

And, with the Taliban, also unlikely to attend, the Bonn meeting may become another exercise in futility – typical of a conflict that has cost thousands of lives and cost many billions of dollars for little result.

The present gloom contrasts sharply with the meeting in Bonn in 2001, in the aftermath of 9/11, when Western nations were buoyant about the prospects of defeating terrorism by attacking its base areas in Afghanistan and Pakistan. There were some successes – the toppling of the Taliban regime then ruling Afghanistan, and the killing of al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in his long-time Pakistan hideout this year.

But with Western economies struggling to cope with crippling levels of debt, and domestic weariness with the war (in the United States mirroring the situation that undermined American will to win in Vietnam four decades ago), there is now a strong desire to escape the quagmire.

President Barack Obama seeks re-election next year and will not need reminding of how an unpopular war (Vietnam) destroyed the political career of an earlier Democratic president, the late Lyndon Johnson.

On the Afghan side, there is anger at the repeated US night-time raids on suspected terrorist targets that have led to many civilian deaths; facing calls to desist, the US has said this is impossible if the resilient Taliban is ultimately to be defeated.

The big question is whether the countries attending the Bonn meeting can achieve unanimity in making the political and economic commitments (to be finalized at a NATO meeting in Chicago next May) that are vital if the present government in Kabul is to have any chance of survival.

Stability remains an elusive commodity. The local security forces currently are incapable of matching the Taliban fighters without a lot of Western stiffening, especially in meeting the US target of military self-sufficiency by 2014 (again, shades of the 'Vietnamization' program that led to the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975).

The national economy is in poor shape and the continuation of widespread endemic poverty remains one of the biggest failures of the Western intervention.

Beyond this, however, lies an even greater concern – the impact on the struggle to contain and destroy terrorism. Despite the deaths of many of their leaders, the various extremist groups like al Qaeda still pose a serious threat.

The Obama Administration has long wanted Pakistan, whose military and economy depend heavily on billions of dollars in American aid, to crack down on the militant groups based on its territory. Indeed, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recently asked Pakistan to bring all militant groups to the negotiating table in order to stabilize conditions in its neighbor.

Pakistan, however, argues that, among all the countries engaged in the war on militancy, it has paid the highest price with thousands of soldiers and police dead. The recent NATO attack raises the possibility that the Pakistanis will refuse to cooperate any more with the West on the terrorism issue.

And, let us not forgot another neighboring country, Iran, which is facing increasing Western sanctions due to its refusal to give up its nuclear ambitions. The recent attack on the British Embassy in Tehran, resulting in the evacuation of all diplomatic staff and the retaliatory closure of the Iranian Embassy in London, shows just how bad things have got.

An immediate response to this came from the EU, which immediately announced tougher economic sanctions – although failing to agree on a suggested embargo of Iranian oil to try and bring the country's economy to its knees.

Thus, a series of incidents and issues pose a danger of creating a vast crescent of volatility stretching unbroken right across South Asia, disastrous not only for the immediate region but for the cause of world peace at a time of great economic vulnerability.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/geoffreymurray.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.