Atoning for Libya: Germany Seeks Low Profile in Syria

http://www.spiegel.de/international/wor ... 19491.html

By Daryl Lindsey

Protests against a possible military strike in Syria have been largely muted in Germany this week. Here, Left Party demonstrators hold a sign: "Bombs don't create peace." Zoom

REUTERS

Protests against a possible military strike in Syria have been largely muted in Germany this week. Here, Left Party demonstrators hold a sign: "Bombs don't create peace."

All eyes are on the international community this week as the US prepares to strike Syria. In Germany, political leaders are keen to avoid a repeat of the embarrassing mistakes made in the run-up to the Libya intervention. Experts say Berlin will offer political support but little else.

Will it come this weekend? Early next week? Or will it follow the G-20 summit in Russia, which begins on Thursday? Few in Germany doubt the likelihood that the United States will launch some kind of strike against Syria in the coming days. British Prime Minister David Cameron may have suffered a bitter defeat by a negative vote in his country's parliament on Thursday, but that likely won't stop the US from acting.

ANZEIGE

In comments made to the New York Times and the Washington Post published on Friday, White House officials began signalling that the US would act unilaterally if it has to. Pentagon officials also stated that a fifth US destroyer carrying dozens of Tomahawk cruise missiles has been moved into the eastern Mediterranean Sea. A red line is a red line -- and most expect Washington to respond in order to protect its credibility.

The growing calls for a military strike are in response to the Aug. 21 chemical weapons attack in Syria -- an attack that White House officials believe was conducted by dictator Bashar Assad's forces. "The message the Americans are sending is that they are planning a small attack against Syrian army installations," says Henning Riecke, the head of the trans-Atlantic relations program and expert on German and US security policy at the German Council on Foreign Relations in Berlin. "The goal here is to cause damage to demonstrate to Assad that if he deploys chemical weapons, then the costs will be greater to him than the benefits. That's how deterrent is intended to work."

'Germany Will Stand in the Way'

Coming as it does just weeks before a national election, the developments create discomfort for incumbent Chancellor Angela Merkel and her Social Democrat challenger, Peer Steinbrück, given that two-thirds of Germans oppose an international military intervention against Syria. Worse yet, what would happen if the US were to ask for anything beyond political support from Germany?

"Election campaigns are a bad time to go to war, and Germany's Western allies know that, too," says Markus Kaim, a security policy expert at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), a Berlin-based think tank that advises the government on foreign policy matters.

More likely, he and other experts say -- particularly given Berlin's abstention from the United Nations Security Council vote on the Libya intervention in 2011 -- Washington is unlikely to ask for much if anything at all.

"At the very most, the Germans will be asked to act friendly and cooperative from the sidelines," says DGAP's Riecke. "In other words, to provide political support for the mission, approach the critics in Moscow and Beijing diplomatically and not undertake any political countermeasures." Earlier this week, Merkel's spokesman called for punitive measures against Syria and "consequences" in the wake of the chemical weapons attack. Riecke said he interpreted this to be an announcement that, "Germany will not stand in the way."

Germany Seeks to Avoid Embarrassment

In the corridors of power in Berlin, the international isolation Germany faced after its abstention from the Libya vote hangs over the current Syria debate like an 800-pound gorilla. At the time, the US, Britain and France moved ahead to establish a no-fly zone in the country without Germany's support.

"It was a mistake and some in (Merkel's) government readily admit that today," says SWP's Kaim. "The lack of coordination with our Western allies and the abstention put German on the same side as Russia and China. It was a meltdown for German politics and the government is now seeking to avoid that."

It's a position shared by General Harald Kujat, the retired former head of Germany's Bundeswehr armed forces. He calls the abstention and subsequent "errors" made by the German government over Libya a "disaster," both militarily and politically. This time around, he says, the only thing the German government will do is "seek to avoid making any major mistakes -- but no more than that."

When asked what Germany could provide if Washington moves to strike next week or after the G-20 summit in St. Petersburg, Kujat has few illusions. "When it comes to geopolitical issues," he says, "Germany plays no role. We are merely extras, and if you're an extra, then you need to make sure you don't disrupt the performance taking place on stage. But disrupt is precisely what we did in Libya."

'A Lot More Time'

Of course, there certainly is some aid, albeit largely symbolic, that the Bundeswehr could provide. DGAP's Riecke points to assistance like the monitoring of additional airspace by German military personnel using AWACs reconnaissance planes, for example. But such aid would likely only become relevant if there were a longer-term intervention in Syria, a prospect few seem to be seriously considering at this time.

In terms of the brief missile strikes the Obama administration appears to be planning, there's not much Germany can do to help. "If the Bundeswehr were to participate, it would require a lot more time," notes Kujat.

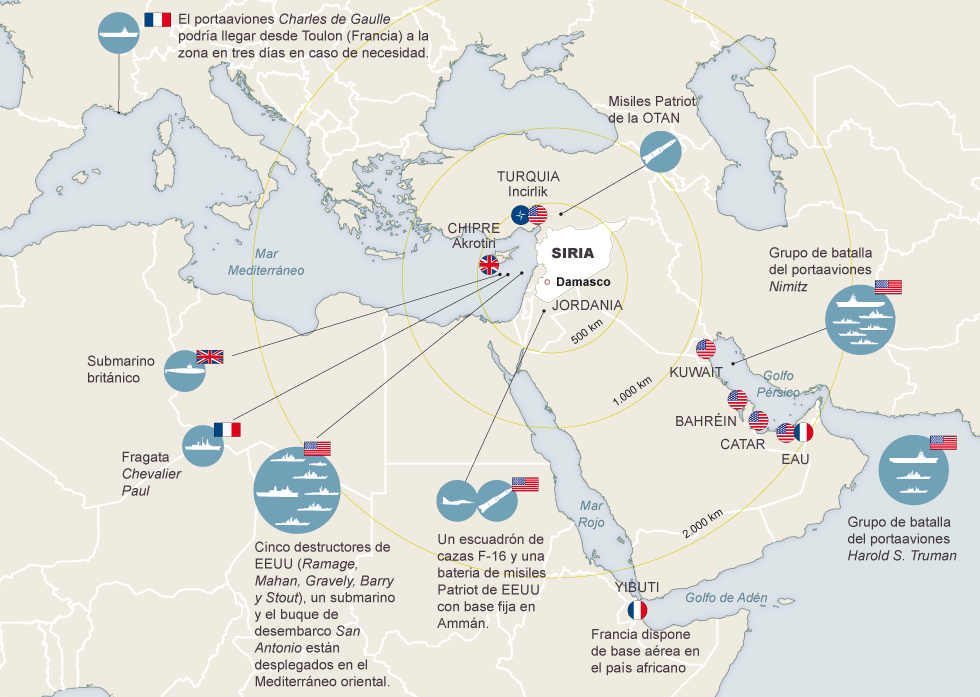

And even then, it would face severe limitations. The Bundeswehr has already been stretched close to its limits with deplyoments in Afghanistan, Kosovo and along Turkey's border, where Bundeswehr troops man Patriot surface-to-air missile batteries as part of NATO operations. It is also hamstrung by physical limitations. Whereas Britain has bases in nearby Cyprus and the US in Crete, Germany has none.

If a longer engagement were to take shape, DGAP's Riecke says there could still be a bit role for Germany to play. "I could imagine that the Germans might be asked to monitor a larger share of the airspace with AWACs planes, but I'm not sure the Americans would really even need that," he says.

Germany Could Offer Its Soft Power

For now, the main thing Germany has to offer is diplomacy -- the soft power it wields as the European Union's largest economy and as a partner of Russia.

Political support is important, "but it is also important that we act constructively in the international bodies where we have seats and votes -- in NATO, at the European Union, which still hasn't stated a position on Syria, and at the G-20 summit next week where we will sit at the same table as the other Western actors, including Russia and the US. At these forums, Germany has the ability to help shape foreign and security policy. The country may not be decisive, but it can still state its position and push for things," former Bundeswehr General Kujat says. Despite strained relations between Merkel and Russian President Vladimir Putin, he says "Germany still has good ties to Russia as well as a very good name in the Arab world."

The point of a strike, argues SWP's Kaim, is to assert pressure on Assad to eschew chemical weapons, but just as importantly to push for movement in Syrian peace talks in Geneva. Kaim sees a possible strike next week as opening a "window of opportunity" for European diplomacy.

"If there is a strike next week, then Damascus, Moscow and Tehran would have to reassess their options," Kaim says. "Wouldn't that be a terrific opportunity for Germany and the EU, together with the British, French or even Polish foreign minister and EU foreign affairs chief Catherine Ashton to say: We're going to fly to Damascus and use this opportunity for a fresh diplomatic start?"

'Broad Consent for the Americans to Take a Step'

There's almost universal consensus that next week's G-20 summit in Russia should be used as an opportunity to seek a deal with Moscow. "Perhaps a compromise is actually possible with Russia," says military observer Kujat. "It's certainly not in the interest of the Russians for Assad to be using chemical weapons against his own people. As Assad supporters, this would discredit the country."

So far, though, there are no signs Moscow is ready to seek a deal. "Russia is against any resolution of the UN Security Council which may contain an option for the use of force," Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Gennady Gatilov said on Friday. The statement came after a UN meeting seeking to come up with a resolution on the Syrian crisis failed to reach any agreement.

US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel said Friday that the Obama administration doesn't want to go it alone, but it appears increasingly likely it will. This time, though, in sharp contrast to the Iraq war, there is far less resistance to the US taking solo action in Syria. Although Germans would like to see a solution take shape at the United Nations Security Council, foreign policy experts note that those efforts have failed so far.

"The Security Council has been dysfunctional and its members have been unable to find agreement on any kind of sensible approach," says trans-Atlantic relations observer Riecke. "Russia blocked that. That's why, mostly in the Western world, there is a large degree of support, acceptance or at least tolerance for the Americans to take a step."