ESTRATÉGIA NAVAL

Moderador: Conselho de Moderação

- Marino

- Sênior

- Mensagens: 15667

- Registrado em: Dom Nov 26, 2006 4:04 pm

- Agradeceu: 134 vezes

- Agradeceram: 630 vezes

Re: ESTRATÉGIA NAVAL

Got Sea Control?

By Captain Victor G. Addison Jr., U.S. Navy and Commander David Dominy, Royal Navy

USNI Image Gallery

U.S. Navy (Joshua J. Wahl)

Classic blue-water naval conflicts are giving way to complex littoral operations involving failed states, piracy, and joint relief operations, forcing the United States to assess sea control. Left, Sailors and Marines on board the amphibious dock landing ship USS Harpers Ferry (LSD-49) in October 2009 pass stores during a vertical replenishment with the Military Sealift Command ship USNS San Jose (TAFS-7) in humanitarian support of the Republic of the Philippines following two major storms.

Pictures

USNI Image Gallery

Google Translate My Page

Gadgets powered by Google

Small Text

Regular Text

Large Text

The United States and United Kingdom have the most powerful combined naval force on the planet. Does this mean we can control the seas where and when we want? Maybe not.

Naval history is replete with tales of victory by great fleets on the high seas. But it is also punctuated by the stunning defeats of many of these same fleets in their adversaries' coastal waters, or littorals. Although it may seem self-evident that a coastal navy would not fare as well in blue-water warfare, the limitations of a blue-water navy in the littorals are less obvious and often unanticipated.

Take, for example, the experience of ancient navies. In 1178 B.C.E., the Egyptians defeated a large fleet of sea raiders that had dominated the Mediterranean for more than 100 years by ambushing them from shore with flaming arrows. In 480 B.C.E., the Greeks conquered a much larger Persian fleet by luring them into the restricted waters of the Straits of Salamis, where they were outmaneuvered and could not bring their superior numbers and firepower to bear.

Flaming arrows have been replaced by antiship missiles, but the principle remains the same: the ability to control blue water does not necessarily apply to the littorals. In coastal waters, an adversary does not require a navy to successfully repel a naval attack. This is one of many reasons why great navies historically have prefered deeper water.

Control vs. Command

Our modern understanding of sea control has its origins in the writings of Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan and Sir Julian Stafford Corbett. Mahan built his theory of "command of the seas" on naval superiority, the concentration of forces, and decisive battles. Corbett subsequently introduced the concept of "control of the seas" as a relative, rather than absolute, condition that applies naval power toward the broader goal of achieving national objectives. According to Corbett, control of the seas is not an end in itself but a means to conduct operations in peace and war that produces effects on land. As our memories of classic blue-water naval battles fade and we find ourselves increasingly engaged in complex littoral operations spanning great distances to counter challenges associated with failing states, regional instability, crime, and violent extremism, the writings of Corbett deserve a closer read.

Recognizing that total control of the seas is not practical, then Vice Admiral Stansfield Turner coined the phrase "sea control" to connote "more realistic control in limited areas and for limited periods of time."1

British Maritime Doctrine applies these boundary conditions and introduces the notion of purpose.

Sea control is the condition in which one has freedom of action to use the sea for one's own purposes in specified areas and for specified periods of time and, where necessary, to deny or limit its use to the enemy. Sea control includes the airspace above the surface and the water volume and seabed below.2

Taking this definition one step further by tying sea control directly to specific military objectives provides greater contrast between the littoral and blue-water cases. In blue water, sea-control challenges are likely to come from enemy fleets with naval objectives focused, in the spirit of Mahan, on decisive battle. In the littorals, sea-control challenges are often asymmetric in nature, with military objectives, such as establishing a sea base or conducting an amphibious landing, tied to the broader context of influencing events on shore. A simple definition of sea control that covers the full range of operations, therefore, is the use of the sea as a maneuver space to achieve military objectives.

Beyond Blue Water

The importance of sea control has been understated in recent years because of our longstanding maritime blue-water supremacy. A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower categorizes sea control as one of the sea services' six expanded core capabilities, but does not distinguish it. With the continuing proliferation of anti-access and area-denial capabilities around the world, the likelihood is increasing that our local sea control will be challenged, particularly in the littorals. Military planners who require naval power to support operations ashore must take this into account.

As Secretary of Defense Robert Gates remarked in an April 2009 address at the U.S. Naval War College, we face potential conflicts that "will range across a broad spectrum of operations and lethality. Where near-peers will use irregular or asymmetric tactics that target our traditional strengths—such as our ability to project power via carrier strike groups. And where non-state actors may have weapons of mass destruction or sophisticated missiles."

These challenges include unpredictable political circumstances that will restrict overseas access, basing, and overflight rights at inopportune moments. The role of sea control as the most fundamental naval capability that facilitates joint and coalition freedom of action is therefore obvious. Retired Major General David Fastabend, then the U.S. Army's director of Strategy, Plans, and Policy, underscored this critical joint force interdependency during Navy-Army Warfighter Talks in 2008 when he observed, "If you can't provide maritime supremacy, we are buying the wrong kind of Army."

Perhaps the most apt question regarding sea control is not, Can we? but, How do we know if we can? Although joint planners depend on sea power to deliver access, mobility, firepower, and 90 percent of joint-force supplies, there is no generally accepted methodology or doctrine to assess our "sea-control potential" during the campaign-design process.

Start with a Framework

In keeping with traditional Pentagon staffing principles, a first step in developing such a methodology would be to propose a subjective analytical framework based on sea-control levels, such as the following:

* Unopposed: Military objectives can be achieved without significant losses.

* Opposed: Military objectives can be achieved, but losses may be significant.

* Denied: Military objectives cannot be achieved and/or there is a high probability of unacceptable losses.

Levels of sea control should be considered in the context of objectives and can be referenced as either an assessment of the operating environment or as a strategy. In this regard, an assessment can be used to define risk and present strategic options to planners in terms of force posture and sequencing. For example, the presence of an adversary's (red) surface action group and shore-based antiship missile batteries may produce a hostile environment for an amphibious landing, but have little impact on allied (blue) submarines and carrier-based aircraft. Allied strategy to successfully execute the amphibious landing could then be to deny the operations area to the red surface action group by using their asymmetric advantage in submarine warfare and to neutralize the missile batteries using their tactical aircraft.

This simple framework may be adequate for a high-level briefing, but planners require more detailed assessment criteria. While there appears to be an infinite range of elements to assess in determining a navy's sea control potential, the following five provide a starting point

* Capacity: The combat power a force can bring to bear in a local operations area—a critical factor in attrition warfare.

* Capability: The attributes a force possesses that determine its potential to disrupt an adversary.

* Information Dominance: The situational understanding required to operate forces with relative advantage under dynamic circumstances.

* Tactical Readiness: A force's ability to perform its assigned missions effectively in battle as a function of tactics, training, and procedures.

* Maneuver Space: The constraints and conditions within which a naval force must operate.

Since these elements are neither discrete nor unique to sea control, it is within the context of the objective that they become relevant. Using the previous example, the allied, or blue, force would have to assess in relative terms, at a minimum, its capacity to wipe out red missile batteries; its capability to disrupt the red surface action group; its tactical readiness to execute the full range of missions culminating in the amphibious landing; its ability to achieve and maintain situational understanding in dynamic conditions; and the impact of the littoral operating environment on red and blue forces. A similar assessment should be conducted from the perspective of the red force.

These elements become increasingly intertwined and difficult to assess when it comes to littoral sea control. A proliferation of disruptive shore-based capabilities can pressure naval forces as they move out of blue water and toward the coast. The at-sea tactical picture becomes more cluttered, making it more difficult to distinguish threats among ambiguous targets. Most important, littoral regions are typically defined by limitations—physical, political, or otherwise—that restrict a naval force's freedom of action. Potentially limitless tactical permutations await the joint sea-control planner.

One method of calibrating a predictive model is to run it against known historical data. By virtue of its overwhelming conventional superiority, the U.S. Navy has operated in a relatively unopposed sea-control environment for many decades and offers limited historical data for developing such a model. Two of America's closest allies, the United Kingdom and Israel, however, have been involved in stressing sea-control cases that are more suitable for analysis.

1982: Britain and Argentina in the Falklands

The 1982 Falklands War is a good example of the challenges navies confront when conducting sea control in the littorals of adversaries at a distance of more than than 8,000 miles. Of the many detailed accounts of the Falklands War, only the memoir of Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward, One Hundred Days, provides the perspective of the task force commander. Woodward notes that "there were several competent organizations which initially suspected the whole operation was doomed." One of these organizations was "the United States Navy, which considered the recapture of the Falkland Islands to be a military impossibility." Although this assessment turned out to be slightly pessimistic, Woodward himself observed that "we fought our way along a knife edge, I realize perhaps more than most that one major mishap, a mine, explosion, a fire, whatever, in either of our two aircraft carriers, would certainly have proven fatal to the whole operation."

A more specific risk estimate from a sea-control assessment would probably not have dissuaded former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher from ordering the recapture of the Falklands, but it might have influenced campaign strategy. It is illustrative to examine the Falklands campaign as two distinct sea-control problems: blue water and littoral. An actual assessment of these phases by a headquarters staff would require subcategories, weighting factors, and a great deal of PowerPoint. What follows is the distilled version of a relative sea-control assessment that would have been provided for senior Royal Navy leadership.

Blue-Water Phase

In the blue-water phase, the British Task Force's objective was to rapidly conduct an unopposed transit to the South Atlantic and establish a 200-nautical-mile radius "tactical exclusion zone" around the Falkland Islands in preparation for an amphibious assault. Argentina's objective was to deny the Royal Navy the use of the sea as maneuver space through disruption and attrition, thereby preventing an amphibious assault.

The Scorecard

Capacity: Each side owned sufficient naval assets to defeat the other, but Argentina had a five-to-one advantage in tactical aircraft that could potentially overwhelm the British Task Force's air-defense capacity. The lack of an overmatch by the United Kingdom in this category, which includes the challenge of an 8,000 nautical mile logistics chain, probably influenced the U.S. Navy's dire assessment of the Royal Navy's chances. Advantage: Argentina.

Capability: Argentina's fighter aircraft had superior speed and maneuverability compared with the United Kingdom's Harriers, but the United States leveled the playing field somewhat by supplying the British with the advanced AIM-9 Sidewinder missile for air-to-air combat. The Argentine Navy had a significant advantage with the French Exocet antiship missile, but their supply was limited. In the Royal Navy's favor, its three nuclear fast-attack submarines provided an asymmetric antiship and intelligence-gathering capability for Woodward's task force. Advantage: Toss-up.

Information Dominance: The Royal Navy received strategic intelligence from the United States and derived a great deal of tactical intelligence from their fast-attack submarines. Advantage: United Kingdom.

Tactical Readiness: The British developed dog-fighting tactics that would greatly increase the kill ratio of the Harriers. Additionally, the Royal Navy placed significant tactical emphasis on protecting its aircraft carriers and using forward-operating fast-attack submarines to threaten the Argentine Navy's "high value units." Advantage: United Kingdom.

Maneuver Space: The Royal Navy planned to exploit the vast sea area around the Falkland Islands to position its fleet for tactical advantage, keeping the carriers out of strike range and forcing the Argentine strike aircraft to fly through defensive missile screens. Advantage: United Kingdom.

Overall assessment of sea-control level for the blue-water phase: Opposed.

The military objective of controlling the seas around the Falklands in advance of the littoral campaign phase would be achievable with acceptable losses.

Littoral Phase

The United Kingdom's objective during the littoral sea-control phase was to conduct an amphibious assault that established an onshore launching pad from which to defeat Argentine forces on the Falkland Islands. The choice of amphibious objective area was based primarily on the desire to conduct an unopposed landing operation using naval escorts in the Falkland Sound to blunt the anticipated Argentine air assault. Argentina's objective was to use air power to deny the British task force the necessary maneuver space to conduct the amphibious assault and disable it.

The Scorecard

Capacity: The same blue-water imbalance of power carried forth to the littorals. Advantage: Argentina.

Capability: Once the British task force moved toward its amphibious objective area, it was squarely within range of Argentina's shore-based tactical aircraft and missile batteries, a potentially decisive asymmetric advantage for Argentina. Advantage: Argentina.

Information Dominance: The Royal Navy's forces would be easier to find and fix within the confines of the littoral battlespace, thereby negating their strategic and tactical intelligence advantage. Advantage: Toss-up.

Tactical Readiness: The British advantage in blue-water tactics and training would not necessarily apply in the littorals, where the highly proficient Argentine Air Force would become a greater factor. Advantage: Toss-up.

Maneuver Space: The British Task Force was severely restricted in its ability to maneuver in the littorals and, specifically, in Falkland Sound. Advantage: Argentina.

Overall assessment of sea-control level for the littoral phase: Denied.

The military objective of controlling the Falkland Sound for the amphibious landing would place the task force well within range of Argentina's air force, so the probability of unacceptable losses was extremely high.

Actual Campaign Summary

During the blue-water phase, the Royal Navy exploited the extensive maneuver space to protect its aircraft carriers from Argentina's 200 jets. Concurrently, Britain's asymmetric undersea warfare advantage became decisive when its fast-attack submarine HMS Conqueror torpedoed Argentina's heavy cruiser General Belgrano. This strategic knock-out punch sidelined the Argentine navy—including its aircraft carrier, the ARA Veinticinco de Mayo—for the rest of the war.

The battle shifted markedly in Argentina's favor during the littoral sea-control phase, because the British task force was constrained by its objective, the amphibious landing, and was forced to operate in the sights of Argentina's modern, shore-based air force. Argentina's potentially decisive asymmetric air-warfare advantage was ultimately squandered by a tactical failure. During the littoral sea-control phase, every single British escort operating in Falkland Sound was hit by bombs dropped from Argentina's air force, but many of the bombs did not explode. Admiral Woodward summarized this aspect of the littoral sea-control phase best when he noted in his memoir, "We lost Sheffield, Coventry, Ardent, Antelope, Atlantic Conveyor, and Sir Galahad," but concluded that if Argentina's bombs had been properly fused for low-level air raids, Britain would have lost the war.

Same Game, New Rules

A new dimension has been added to littoral sea control by what is referred to as "the hybrid threat," which retired Marine Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hoffman defines as any adversary that employs a fusion of "conventional weapons, irregular tactics, terrorism, and criminal behavior in the battle space to obtain their political objectives." For example, the hybrid threat posed by the intersection of Somali pirates and the terrorist organizations al-Shabab and al Qaeda near the Bab-el-Mandeb has provided an unprecedented challenge for Coalition navies struggling to keep one of the world's most strategic oil chokepoints open. Nation states that do not possess the capability to directly challenge powerful navies may also employ hybrid sea-denial strategies. This is particularly relevant if the adversary's objective is not to defeat their enemy in conventional terms, but to undermine political will through a protracted struggle that imposes significant costs.

The 2006 Lebanon War between Israel and Hezbollah provides an example of a struggle for littoral sea control within the context of a hybrid threat. The Israeli Navy possessed a clear overmatch in conventional capabilities and developed its tactics accordingly. There is another perspective—Hezbollah's—that will be considered for this sea-control assessment.

2006: Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon

During the 2006 Lebanon War, the Israeli Navy's objective was to impose a naval blockade to isolate Hezbollah and thus help to advance Israeli defense force operations ashore. Hezbollah's objective was less complicated: inflict damage on a regional superpower, survive the conflict, and win the public relations war. Since Hezbollah doesn't have a navy, this example typifies the "hybrid sea denial" approach that navies may encounter in the littorals.

The Scorecard

Capacity: The Israeli Navy held an absolute capacity overmatch in regular naval forces, but Hezbollah's hybrid forces were not negligible and had to be considered. Advantage: Israel.

Capability: The Israeli Navy clearly overmatched Hezbollah in conventional capabilities. Hezbollah employed hybrid tactics that included missiles, suicide bombers, crime, manipulation of civilian infrastructure, and propaganda. Advantage: Israel.

Information Dominance: The Israeli Navy possessed significant intelligence, command-and-control, and cyber capabilities, but was not aware of Hezbollah's C-802 antiship missiles that could be fired from trucks against naval targets. Since the Israeli Navy had to operate near shore to maintain a blockade, this simplified Hezbollah's targeting problem. Hezbollah also had significant intelligence resources augmented by capabilities from regional allies and was exceptionally media savvy. Advantage: Toss-up.

Tactical Readiness: The Israeli Navy was tactically proficient and well-defended against the C-802 missile when its use was anticipated. Both the Israeli Navy and Hezbollah are very good at what they do. Advantage: Toss-up.

Maneuver Space: The Israeli Navy was constrained by the littoral operating environment, rules of engagement, military doctrine, and international law. Hezbollah's maneuver space was not similarly constrained. Advantage: Hezbollah.

Overall assessment of sea-control level for the 2006 Lebanon War: Opposed.

The Israeli Navy undoubtedly considered its blockade to be an unopposed sea-control operation based on the complete absence of conventional Hezbollah naval capability.

Actual Campaign Summary

The Israeli Navy ship Hanit was severely damaged by a C-802 missile on 14 July 2006. Following a United Nations-brokered ceasefire, the war ended when Israel lifted its naval blockade on 8 September 2006. The chief of the Israeli Navy resigned in 2007. During a panel discussion at the 2009 Surface Navy Association conference, a senior Israeli naval officer advised against spending too much time in the littorals because of the complex threat environment, emphasizing the point that if you don't have to be there, "don't go there."

The Littoral Truth

SIr Julian Corbett was right: to support joint force, national, and even international objectives, we must operate in the littorals. For powerful navies, the most difficult aspect of operating in the littorals is acquiring the necessary mindset and realizing that the default sea-control level is "opposed." It doesn't seem just that our multibillion-dollar ships can be damaged or even sunk by cheap mines, missiles, or skiffs laden with explosives. But we must realistically admit the possibility. History has shown us that in the complicated littoral sea-control environment, losses are not only possible, they are inevitable. Littoral sea control, therefore, needs to be assessed, not assumed, as an important component of campaign design. Powerful navies may not particularly like the idea of operating in the littorals, but it's where the jobs are.

1. Vice Admiral Stansfield Turner, U.S. Navy, "Missions of the U.S. Navy," Naval War College Review, 1974, Vol. XXVI, No. 5., p. 7.

2. BR 1806 British Maritime Doctrine, Third Edition, 2004, p. 289.

Captain Addison is assigned to the staff of the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Operations, Plans and Strategy (N3/N5) as branch head for advanced concepts (N511). He is an oceanographer and former submarine strategic weapons officer.

Commander Dominy is assigned to the Pentagon as the first Royal Navy Liaison Officer to OPNAV N3/N5. A surface warfare officer, he commanded the destroyer HMS Manchester, which was integrated into the USS Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group during operations in the Arabian Gulf.

By Captain Victor G. Addison Jr., U.S. Navy and Commander David Dominy, Royal Navy

USNI Image Gallery

U.S. Navy (Joshua J. Wahl)

Classic blue-water naval conflicts are giving way to complex littoral operations involving failed states, piracy, and joint relief operations, forcing the United States to assess sea control. Left, Sailors and Marines on board the amphibious dock landing ship USS Harpers Ferry (LSD-49) in October 2009 pass stores during a vertical replenishment with the Military Sealift Command ship USNS San Jose (TAFS-7) in humanitarian support of the Republic of the Philippines following two major storms.

Pictures

USNI Image Gallery

Google Translate My Page

Gadgets powered by Google

Small Text

Regular Text

Large Text

The United States and United Kingdom have the most powerful combined naval force on the planet. Does this mean we can control the seas where and when we want? Maybe not.

Naval history is replete with tales of victory by great fleets on the high seas. But it is also punctuated by the stunning defeats of many of these same fleets in their adversaries' coastal waters, or littorals. Although it may seem self-evident that a coastal navy would not fare as well in blue-water warfare, the limitations of a blue-water navy in the littorals are less obvious and often unanticipated.

Take, for example, the experience of ancient navies. In 1178 B.C.E., the Egyptians defeated a large fleet of sea raiders that had dominated the Mediterranean for more than 100 years by ambushing them from shore with flaming arrows. In 480 B.C.E., the Greeks conquered a much larger Persian fleet by luring them into the restricted waters of the Straits of Salamis, where they were outmaneuvered and could not bring their superior numbers and firepower to bear.

Flaming arrows have been replaced by antiship missiles, but the principle remains the same: the ability to control blue water does not necessarily apply to the littorals. In coastal waters, an adversary does not require a navy to successfully repel a naval attack. This is one of many reasons why great navies historically have prefered deeper water.

Control vs. Command

Our modern understanding of sea control has its origins in the writings of Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan and Sir Julian Stafford Corbett. Mahan built his theory of "command of the seas" on naval superiority, the concentration of forces, and decisive battles. Corbett subsequently introduced the concept of "control of the seas" as a relative, rather than absolute, condition that applies naval power toward the broader goal of achieving national objectives. According to Corbett, control of the seas is not an end in itself but a means to conduct operations in peace and war that produces effects on land. As our memories of classic blue-water naval battles fade and we find ourselves increasingly engaged in complex littoral operations spanning great distances to counter challenges associated with failing states, regional instability, crime, and violent extremism, the writings of Corbett deserve a closer read.

Recognizing that total control of the seas is not practical, then Vice Admiral Stansfield Turner coined the phrase "sea control" to connote "more realistic control in limited areas and for limited periods of time."1

British Maritime Doctrine applies these boundary conditions and introduces the notion of purpose.

Sea control is the condition in which one has freedom of action to use the sea for one's own purposes in specified areas and for specified periods of time and, where necessary, to deny or limit its use to the enemy. Sea control includes the airspace above the surface and the water volume and seabed below.2

Taking this definition one step further by tying sea control directly to specific military objectives provides greater contrast between the littoral and blue-water cases. In blue water, sea-control challenges are likely to come from enemy fleets with naval objectives focused, in the spirit of Mahan, on decisive battle. In the littorals, sea-control challenges are often asymmetric in nature, with military objectives, such as establishing a sea base or conducting an amphibious landing, tied to the broader context of influencing events on shore. A simple definition of sea control that covers the full range of operations, therefore, is the use of the sea as a maneuver space to achieve military objectives.

Beyond Blue Water

The importance of sea control has been understated in recent years because of our longstanding maritime blue-water supremacy. A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower categorizes sea control as one of the sea services' six expanded core capabilities, but does not distinguish it. With the continuing proliferation of anti-access and area-denial capabilities around the world, the likelihood is increasing that our local sea control will be challenged, particularly in the littorals. Military planners who require naval power to support operations ashore must take this into account.

As Secretary of Defense Robert Gates remarked in an April 2009 address at the U.S. Naval War College, we face potential conflicts that "will range across a broad spectrum of operations and lethality. Where near-peers will use irregular or asymmetric tactics that target our traditional strengths—such as our ability to project power via carrier strike groups. And where non-state actors may have weapons of mass destruction or sophisticated missiles."

These challenges include unpredictable political circumstances that will restrict overseas access, basing, and overflight rights at inopportune moments. The role of sea control as the most fundamental naval capability that facilitates joint and coalition freedom of action is therefore obvious. Retired Major General David Fastabend, then the U.S. Army's director of Strategy, Plans, and Policy, underscored this critical joint force interdependency during Navy-Army Warfighter Talks in 2008 when he observed, "If you can't provide maritime supremacy, we are buying the wrong kind of Army."

Perhaps the most apt question regarding sea control is not, Can we? but, How do we know if we can? Although joint planners depend on sea power to deliver access, mobility, firepower, and 90 percent of joint-force supplies, there is no generally accepted methodology or doctrine to assess our "sea-control potential" during the campaign-design process.

Start with a Framework

In keeping with traditional Pentagon staffing principles, a first step in developing such a methodology would be to propose a subjective analytical framework based on sea-control levels, such as the following:

* Unopposed: Military objectives can be achieved without significant losses.

* Opposed: Military objectives can be achieved, but losses may be significant.

* Denied: Military objectives cannot be achieved and/or there is a high probability of unacceptable losses.

Levels of sea control should be considered in the context of objectives and can be referenced as either an assessment of the operating environment or as a strategy. In this regard, an assessment can be used to define risk and present strategic options to planners in terms of force posture and sequencing. For example, the presence of an adversary's (red) surface action group and shore-based antiship missile batteries may produce a hostile environment for an amphibious landing, but have little impact on allied (blue) submarines and carrier-based aircraft. Allied strategy to successfully execute the amphibious landing could then be to deny the operations area to the red surface action group by using their asymmetric advantage in submarine warfare and to neutralize the missile batteries using their tactical aircraft.

This simple framework may be adequate for a high-level briefing, but planners require more detailed assessment criteria. While there appears to be an infinite range of elements to assess in determining a navy's sea control potential, the following five provide a starting point

* Capacity: The combat power a force can bring to bear in a local operations area—a critical factor in attrition warfare.

* Capability: The attributes a force possesses that determine its potential to disrupt an adversary.

* Information Dominance: The situational understanding required to operate forces with relative advantage under dynamic circumstances.

* Tactical Readiness: A force's ability to perform its assigned missions effectively in battle as a function of tactics, training, and procedures.

* Maneuver Space: The constraints and conditions within which a naval force must operate.

Since these elements are neither discrete nor unique to sea control, it is within the context of the objective that they become relevant. Using the previous example, the allied, or blue, force would have to assess in relative terms, at a minimum, its capacity to wipe out red missile batteries; its capability to disrupt the red surface action group; its tactical readiness to execute the full range of missions culminating in the amphibious landing; its ability to achieve and maintain situational understanding in dynamic conditions; and the impact of the littoral operating environment on red and blue forces. A similar assessment should be conducted from the perspective of the red force.

These elements become increasingly intertwined and difficult to assess when it comes to littoral sea control. A proliferation of disruptive shore-based capabilities can pressure naval forces as they move out of blue water and toward the coast. The at-sea tactical picture becomes more cluttered, making it more difficult to distinguish threats among ambiguous targets. Most important, littoral regions are typically defined by limitations—physical, political, or otherwise—that restrict a naval force's freedom of action. Potentially limitless tactical permutations await the joint sea-control planner.

One method of calibrating a predictive model is to run it against known historical data. By virtue of its overwhelming conventional superiority, the U.S. Navy has operated in a relatively unopposed sea-control environment for many decades and offers limited historical data for developing such a model. Two of America's closest allies, the United Kingdom and Israel, however, have been involved in stressing sea-control cases that are more suitable for analysis.

1982: Britain and Argentina in the Falklands

The 1982 Falklands War is a good example of the challenges navies confront when conducting sea control in the littorals of adversaries at a distance of more than than 8,000 miles. Of the many detailed accounts of the Falklands War, only the memoir of Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward, One Hundred Days, provides the perspective of the task force commander. Woodward notes that "there were several competent organizations which initially suspected the whole operation was doomed." One of these organizations was "the United States Navy, which considered the recapture of the Falkland Islands to be a military impossibility." Although this assessment turned out to be slightly pessimistic, Woodward himself observed that "we fought our way along a knife edge, I realize perhaps more than most that one major mishap, a mine, explosion, a fire, whatever, in either of our two aircraft carriers, would certainly have proven fatal to the whole operation."

A more specific risk estimate from a sea-control assessment would probably not have dissuaded former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher from ordering the recapture of the Falklands, but it might have influenced campaign strategy. It is illustrative to examine the Falklands campaign as two distinct sea-control problems: blue water and littoral. An actual assessment of these phases by a headquarters staff would require subcategories, weighting factors, and a great deal of PowerPoint. What follows is the distilled version of a relative sea-control assessment that would have been provided for senior Royal Navy leadership.

Blue-Water Phase

In the blue-water phase, the British Task Force's objective was to rapidly conduct an unopposed transit to the South Atlantic and establish a 200-nautical-mile radius "tactical exclusion zone" around the Falkland Islands in preparation for an amphibious assault. Argentina's objective was to deny the Royal Navy the use of the sea as maneuver space through disruption and attrition, thereby preventing an amphibious assault.

The Scorecard

Capacity: Each side owned sufficient naval assets to defeat the other, but Argentina had a five-to-one advantage in tactical aircraft that could potentially overwhelm the British Task Force's air-defense capacity. The lack of an overmatch by the United Kingdom in this category, which includes the challenge of an 8,000 nautical mile logistics chain, probably influenced the U.S. Navy's dire assessment of the Royal Navy's chances. Advantage: Argentina.

Capability: Argentina's fighter aircraft had superior speed and maneuverability compared with the United Kingdom's Harriers, but the United States leveled the playing field somewhat by supplying the British with the advanced AIM-9 Sidewinder missile for air-to-air combat. The Argentine Navy had a significant advantage with the French Exocet antiship missile, but their supply was limited. In the Royal Navy's favor, its three nuclear fast-attack submarines provided an asymmetric antiship and intelligence-gathering capability for Woodward's task force. Advantage: Toss-up.

Information Dominance: The Royal Navy received strategic intelligence from the United States and derived a great deal of tactical intelligence from their fast-attack submarines. Advantage: United Kingdom.

Tactical Readiness: The British developed dog-fighting tactics that would greatly increase the kill ratio of the Harriers. Additionally, the Royal Navy placed significant tactical emphasis on protecting its aircraft carriers and using forward-operating fast-attack submarines to threaten the Argentine Navy's "high value units." Advantage: United Kingdom.

Maneuver Space: The Royal Navy planned to exploit the vast sea area around the Falkland Islands to position its fleet for tactical advantage, keeping the carriers out of strike range and forcing the Argentine strike aircraft to fly through defensive missile screens. Advantage: United Kingdom.

Overall assessment of sea-control level for the blue-water phase: Opposed.

The military objective of controlling the seas around the Falklands in advance of the littoral campaign phase would be achievable with acceptable losses.

Littoral Phase

The United Kingdom's objective during the littoral sea-control phase was to conduct an amphibious assault that established an onshore launching pad from which to defeat Argentine forces on the Falkland Islands. The choice of amphibious objective area was based primarily on the desire to conduct an unopposed landing operation using naval escorts in the Falkland Sound to blunt the anticipated Argentine air assault. Argentina's objective was to use air power to deny the British task force the necessary maneuver space to conduct the amphibious assault and disable it.

The Scorecard

Capacity: The same blue-water imbalance of power carried forth to the littorals. Advantage: Argentina.

Capability: Once the British task force moved toward its amphibious objective area, it was squarely within range of Argentina's shore-based tactical aircraft and missile batteries, a potentially decisive asymmetric advantage for Argentina. Advantage: Argentina.

Information Dominance: The Royal Navy's forces would be easier to find and fix within the confines of the littoral battlespace, thereby negating their strategic and tactical intelligence advantage. Advantage: Toss-up.

Tactical Readiness: The British advantage in blue-water tactics and training would not necessarily apply in the littorals, where the highly proficient Argentine Air Force would become a greater factor. Advantage: Toss-up.

Maneuver Space: The British Task Force was severely restricted in its ability to maneuver in the littorals and, specifically, in Falkland Sound. Advantage: Argentina.

Overall assessment of sea-control level for the littoral phase: Denied.

The military objective of controlling the Falkland Sound for the amphibious landing would place the task force well within range of Argentina's air force, so the probability of unacceptable losses was extremely high.

Actual Campaign Summary

During the blue-water phase, the Royal Navy exploited the extensive maneuver space to protect its aircraft carriers from Argentina's 200 jets. Concurrently, Britain's asymmetric undersea warfare advantage became decisive when its fast-attack submarine HMS Conqueror torpedoed Argentina's heavy cruiser General Belgrano. This strategic knock-out punch sidelined the Argentine navy—including its aircraft carrier, the ARA Veinticinco de Mayo—for the rest of the war.

The battle shifted markedly in Argentina's favor during the littoral sea-control phase, because the British task force was constrained by its objective, the amphibious landing, and was forced to operate in the sights of Argentina's modern, shore-based air force. Argentina's potentially decisive asymmetric air-warfare advantage was ultimately squandered by a tactical failure. During the littoral sea-control phase, every single British escort operating in Falkland Sound was hit by bombs dropped from Argentina's air force, but many of the bombs did not explode. Admiral Woodward summarized this aspect of the littoral sea-control phase best when he noted in his memoir, "We lost Sheffield, Coventry, Ardent, Antelope, Atlantic Conveyor, and Sir Galahad," but concluded that if Argentina's bombs had been properly fused for low-level air raids, Britain would have lost the war.

Same Game, New Rules

A new dimension has been added to littoral sea control by what is referred to as "the hybrid threat," which retired Marine Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hoffman defines as any adversary that employs a fusion of "conventional weapons, irregular tactics, terrorism, and criminal behavior in the battle space to obtain their political objectives." For example, the hybrid threat posed by the intersection of Somali pirates and the terrorist organizations al-Shabab and al Qaeda near the Bab-el-Mandeb has provided an unprecedented challenge for Coalition navies struggling to keep one of the world's most strategic oil chokepoints open. Nation states that do not possess the capability to directly challenge powerful navies may also employ hybrid sea-denial strategies. This is particularly relevant if the adversary's objective is not to defeat their enemy in conventional terms, but to undermine political will through a protracted struggle that imposes significant costs.

The 2006 Lebanon War between Israel and Hezbollah provides an example of a struggle for littoral sea control within the context of a hybrid threat. The Israeli Navy possessed a clear overmatch in conventional capabilities and developed its tactics accordingly. There is another perspective—Hezbollah's—that will be considered for this sea-control assessment.

2006: Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon

During the 2006 Lebanon War, the Israeli Navy's objective was to impose a naval blockade to isolate Hezbollah and thus help to advance Israeli defense force operations ashore. Hezbollah's objective was less complicated: inflict damage on a regional superpower, survive the conflict, and win the public relations war. Since Hezbollah doesn't have a navy, this example typifies the "hybrid sea denial" approach that navies may encounter in the littorals.

The Scorecard

Capacity: The Israeli Navy held an absolute capacity overmatch in regular naval forces, but Hezbollah's hybrid forces were not negligible and had to be considered. Advantage: Israel.

Capability: The Israeli Navy clearly overmatched Hezbollah in conventional capabilities. Hezbollah employed hybrid tactics that included missiles, suicide bombers, crime, manipulation of civilian infrastructure, and propaganda. Advantage: Israel.

Information Dominance: The Israeli Navy possessed significant intelligence, command-and-control, and cyber capabilities, but was not aware of Hezbollah's C-802 antiship missiles that could be fired from trucks against naval targets. Since the Israeli Navy had to operate near shore to maintain a blockade, this simplified Hezbollah's targeting problem. Hezbollah also had significant intelligence resources augmented by capabilities from regional allies and was exceptionally media savvy. Advantage: Toss-up.

Tactical Readiness: The Israeli Navy was tactically proficient and well-defended against the C-802 missile when its use was anticipated. Both the Israeli Navy and Hezbollah are very good at what they do. Advantage: Toss-up.

Maneuver Space: The Israeli Navy was constrained by the littoral operating environment, rules of engagement, military doctrine, and international law. Hezbollah's maneuver space was not similarly constrained. Advantage: Hezbollah.

Overall assessment of sea-control level for the 2006 Lebanon War: Opposed.

The Israeli Navy undoubtedly considered its blockade to be an unopposed sea-control operation based on the complete absence of conventional Hezbollah naval capability.

Actual Campaign Summary

The Israeli Navy ship Hanit was severely damaged by a C-802 missile on 14 July 2006. Following a United Nations-brokered ceasefire, the war ended when Israel lifted its naval blockade on 8 September 2006. The chief of the Israeli Navy resigned in 2007. During a panel discussion at the 2009 Surface Navy Association conference, a senior Israeli naval officer advised against spending too much time in the littorals because of the complex threat environment, emphasizing the point that if you don't have to be there, "don't go there."

The Littoral Truth

SIr Julian Corbett was right: to support joint force, national, and even international objectives, we must operate in the littorals. For powerful navies, the most difficult aspect of operating in the littorals is acquiring the necessary mindset and realizing that the default sea-control level is "opposed." It doesn't seem just that our multibillion-dollar ships can be damaged or even sunk by cheap mines, missiles, or skiffs laden with explosives. But we must realistically admit the possibility. History has shown us that in the complicated littoral sea-control environment, losses are not only possible, they are inevitable. Littoral sea control, therefore, needs to be assessed, not assumed, as an important component of campaign design. Powerful navies may not particularly like the idea of operating in the littorals, but it's where the jobs are.

1. Vice Admiral Stansfield Turner, U.S. Navy, "Missions of the U.S. Navy," Naval War College Review, 1974, Vol. XXVI, No. 5., p. 7.

2. BR 1806 British Maritime Doctrine, Third Edition, 2004, p. 289.

Captain Addison is assigned to the staff of the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Operations, Plans and Strategy (N3/N5) as branch head for advanced concepts (N511). He is an oceanographer and former submarine strategic weapons officer.

Commander Dominy is assigned to the Pentagon as the first Royal Navy Liaison Officer to OPNAV N3/N5. A surface warfare officer, he commanded the destroyer HMS Manchester, which was integrated into the USS Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group during operations in the Arabian Gulf.

"A reconquista da soberania perdida não restabelece o status quo."

Barão do Rio Branco

Barão do Rio Branco

- Andre Correa

- Sênior

- Mensagens: 4891

- Registrado em: Qui Out 08, 2009 10:30 pm

- Agradeceu: 890 vezes

- Agradeceram: 241 vezes

- Contato:

Re: ESTRATÉGIA NAVAL

Se o Brasil tivesse se envolvido directamente no conflito das Malvinas, teriam os EUA feito o mesmo a favor dos britânicos?

Audaces Fortuna Iuvat

- Marino

- Sênior

- Mensagens: 15667

- Registrado em: Dom Nov 26, 2006 4:04 pm

- Agradeceu: 134 vezes

- Agradeceram: 630 vezes

Re: ESTRATÉGIA NAVAL

Plano Brasil

Mísseis Antinavios

13/06/2010

Autor: Bosco

Plano Brasil

Enquanto a visão de uma invasão de milhares de tanques aterrorizava a mente dos estrategistas ocidentais, a visão de centenas de navios capitaneados por porta-aviões gigantescos aterrorizava os estrategistas da ex-URSS.

Como diz um velho ditado, “a necessidade é a mãe da invenção”, e em relação à tecnologia militar não é diferente. Logicamente o “ocidente” se esmerou na luta antitanque e os soviéticos na luta antinavio.

Até a SGM o principal meio de atacar navios era o canhão, o torpedo e as bombas, respectivamente por navios, submarinos e aviões. Isso mudou a partir da década de sessenta com a introdução em larga escala pela URSS do míssil antinavio.

Já na época da SGM houve a introdução de armas guiadas lançadas por bombardeiros na tentativa de atingir navios, mas a tecnologia se mostrou tardia para influir no conflito de modo contundente, tornado-se madura só a partir da década de 60.

Foi só após o ataque ao destróier Eilat por mísseis Styx de fabricação russa lançados de lanchas egípcias na Guerra dos Seis Dias (1967) que o ocidente se deu conta, surpreso, que havia um imenso gap tecnológico com a URSS em relação à “mísseis de cruzeiro antinavios” (ASCM).

Os soviéticos estavam claramente na dianteira dessa corrida já que a OTAN, na mesma época, não possuía nenhum míssil antinavio dedicado.

Míssil Styx de origem russa.

Logo o “ocidente” arregaçou as mangas e se pôs a desenvolver seus “produtos”, e logo também, se viu a diferença da doutrina adotada pela URSS e pelo Ocidente, tendo em vista que os primeiros tinham como objetivo neutralizar uma armada sob a proteção de super porta-aviões.

Ou seja, para lograr êxito os mísseis soviéticos deveriam ter longo alcance, devido à cobertura aérea fornecida por um porta-aviões. Deveriam também ter uma ogiva excepcionalmente grande para poderem atingir de forma contundente um navio com mais de 60.000 toneladas de deslocamento e suas escoltas que em geral deslocavam mais de 10.000 t.

Tais requisitos operacionais fizeram com que os mísseis antinavios soviéticos assumissem um tamanho avantajado tendo em vista a conciliação da necessidade com a tecnologia disponível na época.

A Marinha Soviética, embora extremamente poderosa, se valia de seus submarinos para “projetar força” em detrimento dos navios de superfície, que tinham pouca expressão estratégica, e em geral não estavam sob o guarda chuva protetor de um porta-aviões. Tais características moldaram os mísseis ocidentais de modo a lhes conferir menores dimensões que seus congêneres do outro lado da Cortina de Ferro.

A ABORDAGEM SOVIÉTICA/RUSSA

Os soviéticos sempre deram ênfase a mísseis com poderosas ogivas e alcances que invariavelmente superam as 150 milhas náuticas.

Há uma variedade de opções que vão desde os subsônicos até os supersônicos, lançados por aeronaves, navios, submarinos e lançadores terrestres móveis.

Comparação do míssil russo SS-N-19 com um caça F-16.

Também, todos os sistemas de propulsão disponíveis foram utilizados, desde o foguete líquido, o foguete sólido, passando pelos turbopropulsores e motores ramjet.

Em geral são mísseis pesados e de grande alcance. Alguns chegam a 7 toneladas e alcançam 600 km.

Também são os únicos até agora a operarem mísseis antinavios supersônicos, como o AS-4 lançado pelo Backfire da década de 80 e os famosos SS-N-22 e SS-N-26, entre muitos outros. Só agora outros países os seguem, como a Índia, Taiwan e Japão.

Míssil russo SS-N-22

Enquanto a OTAN tinha no avião o vetor mais apropriado para ataques de grande alcance, os soviéticos, e depois os russos, tinham no poder de seus mísseis seu grande trunfo.

Para lograr êxito contra os grandes porta-aviões americanos os mísseis russos tinham que ter grande alcance e uma pesada ogiva que não raro chegava a 1 tonelada. A maioria dos mísseis tinha também uma versão dotada de ogiva nuclear.

Mísseis com grandes ogivas e grande alcance ficavam pesados e grandes, portanto, fáceis de serem detectado e interceptados.

Para tentar vencer as defesas de uma força tarefa capitaneado por um porta-aviões e sob o manto protetor do Sistema AEGIS a abordagem escolhida foi um incremento na velocidade, de modo a reduzir o tempo de reação da defesa.

Com esta foto podemos observar as dimensões dos lançadores de mísseis SS-N-12.

Míssil SS-N-12 Sandbox

Enquanto o Ocidente desenvolvia pequenos mísseis subsônicos com capacidade “sea skimming”, os soviéticos desenvolviam grandes mísseis supersônicos, alguns chegando a Mach 3, guiados por sistema inercial e com cabeça de busca autônoma baseada em um radar ativo, capacidade “fire-and-forget” e alcance OTH (além do horizonte).

A combinação de mísseis de grandes dimensões e velocidade supersônica trouxe alguns inconvenientes como, por exemplo, uma maior assinatura radar e térmica e uma menor capacidade de manobra.

Navio com lançadores de mísseis SS-N-12.

Outra característica da doutrina russa é o “ataque de saturação” que visa sobrecarregar as defesas do “grupo tarefa”.

Míssil supersônico russo SS-N-26

Do lado ocidental o míssil Tomahawk em sua versão antinavio (TASM) dos anos 80 foi o que mais se identificou com a doutrina soviética/russa. Tinha um alcance de 500 km e uma ogiva de 450 quilos.

Míssil Brahmos indiano baseado no SS-N-26 russo.

Ainda hoje o Tomahawk na sua versão Block IV é o míssil ocidental com capacidade antinavio de maior alcance, superando inclusive os grandes mísseis russos. Chega a 1000 milhas náuticas.

Mísseis soviéticos/russos (designação da OTAN):

• SS-N-1 Scrubber

• SS-N-2 Styx

• SS-N-3 Shaddock

• SS-N-7 Starbright

• SS-N-9 Siren

• SS-N-12 Sandbox

• SS-N-19 Shipwreck (P-700 Granit)

• SS-N-22 / AS-X-22 Sunburn (Moskit)

• SS-N-25 / AS-20 Switchblade (Harpoonski)

• SS-NX-26 Yakhont / Brahmos

• SS-N-27 (P-900 Klub)

• AS-1 Kennel

• AS-2 Kipper

• AS-4 Kitchen

• AS-5 Kelt

• AS-6 Kingfish

• AS-16 Kickback

• AS-17 Krypton

• AS-18 Kazoo

O CONCEITO OCIDENTAL

Já no lado ocidental, motivado pelo incidente do Eilat, e tendo em vista se contrapor à Marinha Soviética que em geral não estava sob a proteção de um porta-aviões, a tendência foi no sentido de desenvolver mísseis de menor tamanho, menor alcance e “pequenas” ogivas.

Dois mísseis se sobressaíram no Ocidente, o Exocet francês e o Harpoon americano. Esses dois exemplos resumem a doutrina ocidental em relação a mísseis anti-navios. Possuem capacidade OTH (além do horizonte), operam no modo LOAL (travamento após o lançamento), são subsônicos, de pequenas dimensões, pesando menos que 700 quilos, ogivas aptas a neutralizar navios de menor tonelagem (6000 t), guiados por um sistema inercial até um ponto pré-determinado onde ativam seu buscador autônomo baseado em um radar ativo miniaturizado e possuem perfil de vôo “sea skimming”, usando o “fundo” para enganar o radar e reduzir o tempo de reação da defesa.

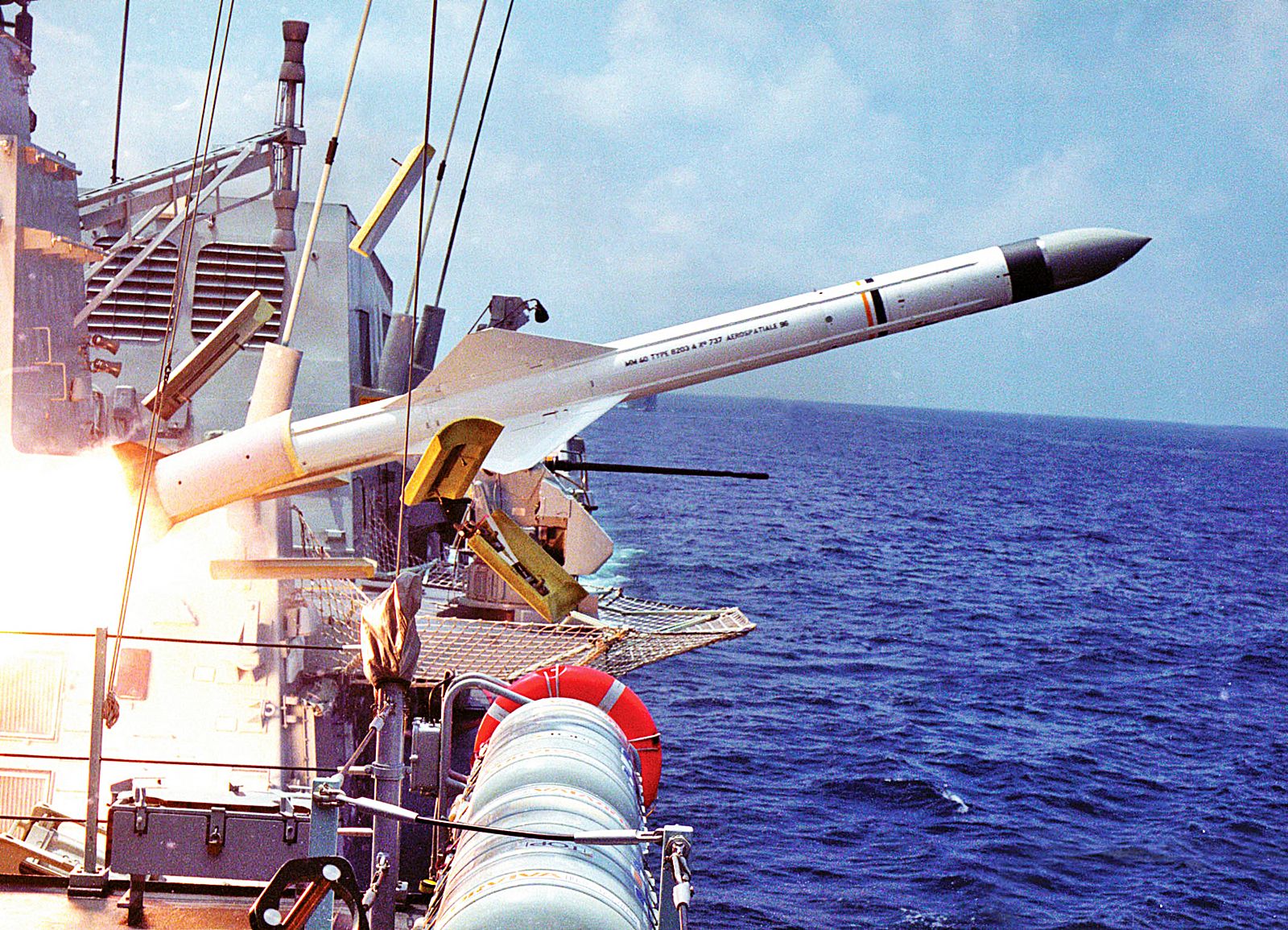

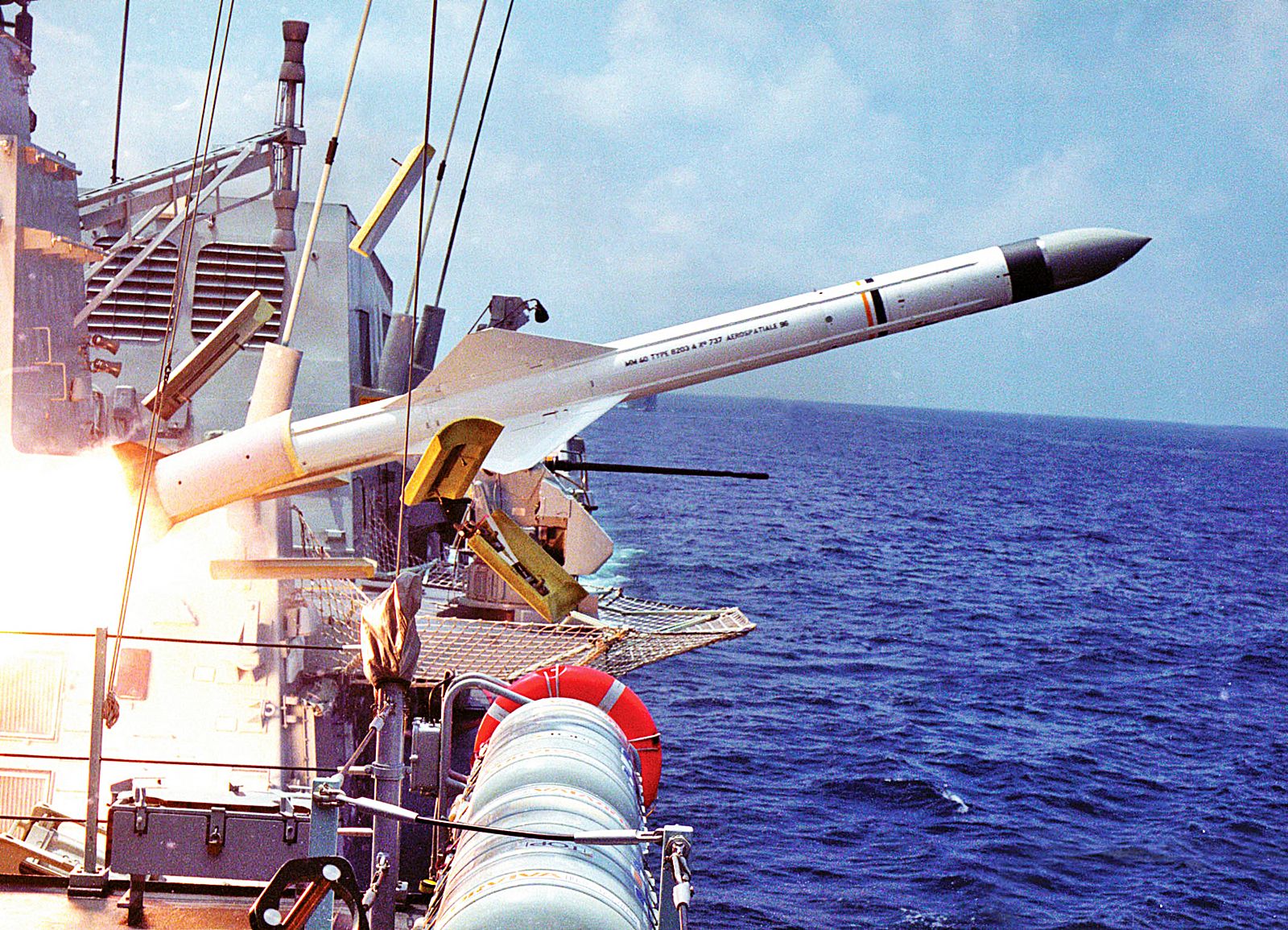

O Exocet ficou famoso na Guerra das Malvinas nas mãos dos argentinos, conseguindo atingir algumas unidades britânicas. É um pequeno míssil subsônico, guiado por radar ativo, com motor foguete sólido e alcance em torno de 70 km. Pode ser lançado de navios, submarinos submersos, aviões de asa fixa, helicóptero de grande porte e plataformas costeiras.

O Harpoon tem o dobro do alcance e é propulsado por um turbojato miniaturizado. Também é subsônico, guiado por radar ativo, de peso leve, reduzida assinatura térmica e radar e grande capacidade de manobra, podendo inclusive efetuar manobras terminais tipo pop-up.

Míssil Harpoon americano.

Ao contrário dos grandes mísseis russos com ênfase anti porta-aviões, os mísseis antinavios ocidentais são compatíveis com caças de pequeno porte e alguns são disparados inclusive por tubos de torpedos convencionais de submarinos.

A capacidade OTH (além do horizonte) exige que o alvo seja designado por uma plataforma avançada, como por exemplo, um helicóptero ou um avião de patrulha marítima.

Mísseis antinavios subsônicos com alcance extremamente grande, por volta de 100 milhas náuticas, obriga a adoção de um sistema de data-link para que possam receber atualizações da posição do navio alvo em tempo real sob pena de não conseguirem detectá-lo nas coordenadas previstas.

Míssil russo SS-N-25

Vale salientar que mísseis com características ocidentais têm sido desenvolvidos e produzidos também na Rússia para armar navios de pequena tonelagem e aviões, sendo o SS-N-25 (Kh-35) um exemplo.

Mísseis “ocidentais”:

• Exocet

• Exocet Block 3

• Harpoon

• RBS15

• Otomat

• NSM

• Gabriel

• Penguin

• Maverick F

• SLAM-ER

• Kormoran

• Sea Eagle

• Tomahawk Block IV (?)

• “JSOW C-1 “

• XASM-3

MÍSSEIS DE PEQUENO PORTE LANÇADOS DE HELICÓPTEROS

O helicóptero é um meio imprescindível nas operações de guerra moderna. Nas operações navais não é diferente e ele desempenha as mais diversas funções que vão desde o resgate, esclarecimento, luta antisubmarina e guerra antisuperfície.

Míssil Sea Skua lançado de helicópteros.

Na função antisuperfície ele é um meio extremamente valioso tanto para esclarecimento e designação de alvos além do horizonte como no ataque direto a meios flutuantes com seus armamentos próprios.

Para cumprir com eficiência essa função foram desenvolvidos vários mísseis antinavios de menor porte e alcance. A grande maioria, propulsados por motores foguetes já que não se espera desses mísseis terem um alcance muito grande.

Em relação aos sistemas de orientação há uma maior variedade, tais como os buscadores térmicos, imagem infravermelha, laser semi-ativo, radar ativo, radar semi-ativo e CLOS com link de radiofreqüência.

Mísseis dessa classe, em geral, têm menos de 400 kg e um alcance máximo em torno de 30 km.

AGM-114M Hellfire

Alguns são oriundos de mísseis antitanques pesados. Um exemplo é o Hellfire II (AGM-114M) guiado por “laser semi-ativo” que pesa 45 kg e tem alcance de 9 km.

Embora não tenham sido projetados para atacarem navios de médio e grande porte, eles podem ser úteis mesmo contra estes se usados no conceito “mission killer” em que o míssil não causa danos capazes de neutralizar um navio de forma definitiva, mas causa a degradação ou a completa perda da sua capacidade operacional, por atingir pontos vitais, tais como, antenas de radar, lançadores de mísseis, etc.

Míssil Exocet de origem francesa. Ficou famoso nas mãos dos argentinos na Guerra das Malvinas.

Uma exceção à regra é o AS-39 Exocet que embora pesando em torno de 700 kg pode ser lançado de helicópteros de maior porte como por exemplo o SH-3.

Esses mísseis assumiram uma grande importância nas operações navais costeiras e alguns inclusive podem ser lançados por navios de pequena tonelagem ou mesmo de plataformas terrestres.

Míssil Penguin lançado de helicóptero.

Hoje, a tendência aponta para mísseis de dupla função, com capacidade antinavio e contra alvos terrestres móveis.

Mísseis de pequeno porte lançados por helicópteros:

• AS-12

• Sea Skua

• Maverick F

• Penguin

• NSM

• Sea Killer

• AS15TT

• Hellfire II (AGM-114M)

• Exocet AM-39

OPERAÇÕES LITORÂNEAS

Durante toda a época da Guerra Fria os estrategistas pensavam a guerra naval em termos de “alto mar”, onde frotas navais se enfrentariam aos moldes das grandes batalhas da SGM.

Com a dissolução da União Soviética em 1991 e o fim da Guerra Fria e mais ainda, após o fatídico “11 de Setembro”, houve a percepção que o futuro da guerra naval seria com forças assimétricas se enfrentando na faixa litorânea.

Tal mudança de paradigma trouxe uma inevitável reformulação da doutrina e consequentemente, do equipamento.

Num primeiro momento se deu a impressão que os mísseis antinavios usados pela OTAN e pela antiga URSS estavam irremediavelmente condenados já que eram aptos a operarem em mar aberto e com pouca utilidade contra pequenas e velozes embarcações na congestionada faixa costeira.

Forçosamente os mísseis teriam que se adaptar. Essa adaptação não tardou.

Com a introdução de sistemas de navegação de precisão por satélite, como por exemplo, o GPS, que usa uma “constelação” de satélites NAVSTAR para prover a posição em tempo real de qualquer objeto no solo ou no ar com erro menor que 10 metros, foi possível reintroduzir o míssil antinavio na ordem do dia.

Tal precisão, possibilitada pelo GPS e similares, permite que mísseis possam seguir caminhos predeterminados por vários pontos de baliza de modo a contornarem acidentes geográficos comuns no litoral e atingirem seus alvos com precisão.

De quebra se ganhou a possibilidade desses mísseis antinavios serem usados inclusive contra alvos no solo já que os sistemas de navegação por satélite, combinados com sistemas de navegação inercial, permitem que alvos fixos sejam atingidos com precisão.

COMO ULTRAPASSAR AS DEFESAS DE UM NAVIO DE GUERRA?

Há meio século essa pergunta tem sido feita e muito esforço tem sido desprendido para respondê-la.

Enquanto os grandes mísseis soviéticos se desenvolveram mais no sentido de aumentarem sua velocidade tentando reduzir o tempo de reação, no lado ocidental a abordagem foi no sentido de manter o míssil o mais discreto possível, com pequenas dimensões e velocidade subsônica.

A velocidade subsônica e ogivas de menor tamanho permitem mísseis menores. Também possibilita um incremento na capacidade de manobra, o que pode ser usado para ludibriar os sistemas defensivos.

Um míssil subsônico em geral é propulsado por turbojatos ou turbofans, o que permite uma excelente relação de massa x alcance x ogiva, além de facilitar a discrição pela baixa emissão térmica.

Outra “abordagem” é o ataque de saturação. Vários mísseis atacando simultaneamente e, na dependência das características defensivas do navio alvo, vindo de uma mesma direção ou de direções diferentes, podem saturar a defesa de modo a que algum atinja seu objetivo, mesmo contra uma defesa consistente.

Hoje é comum em algumas regiões do globo ver navios armados com um grande número de mísseis, bem acima das tradicionais oito unidades.

Já o perfil de vôo “sea skimming” ficou mundialmente famoso quando na Guerra das Malvinas pelo uso do míssil Exocet pelos Argentinos, que era provido de tal capacidade.

Voar a poucos metros da superfície do mar foi e ainda é um dos meios mais usados para possibilitar o ocultamento do míssil, reduzindo o tempo de reação das defesas.

Para tanto o míssil deve possuir um altímetro de radar (ou laser) e software compatível. O inconveniente é que o vôo em altitude tão baixa (3 metros) aumenta o arrasto e, portanto, reduz o alcance.

A “velocidade supersônica” é outro recurso que os projetistas de mísseis antinavios adotam, para atingi-la, necessita-se de propulsores gastadores de combustível, como por exemplo, ramjets, foguetes líquidos, turbojatos com pós-combustores, etc. Em geral a relação massa x alcance nesses mísseis não é muito satisfatória se comparada aos subsônicos, o que obriga células grandes e mísseis pesados. Se o objetivo do míssil supersônico for “neutralizar” um Nimitz, também exige uma grande ogiva. Ou seja, no final o míssil está do tamanho de um F-5 Tiger.

Outro inconveniente da velocidade supersônica é a assinatura térmica exagerada, tanto devido ao atrito como devido à grande emissão de chamas do propulsor.

A manobrabilidade também é restrita em mísseis supersônicos, o que, entre outros fatores, limita seu uso em operações litorâneas e facilita a interceptação.

Na década de 80 tanto os EUA quanto a França desenvolveram e testaram mísseis antinavios supersônicos, mas não chegaram a ser produzidos.

O Míssil supersônico japonês XASM-3.

O Japão está desenvolvendo um míssil antinavio supersônico “peso leve”, o XASM-3, capaz de ser lançado de um F-16, a exemplo do “Krypton” russo. A Índia desenvolveu o Brahmos baseado no SS-N-26 russo e Taiwan por sua vez se baseou no SS-N-22 para desenvolver seu Hsiung Feng 3.

Por último temos a “furtividade”. Com o desenvolvimento e a generalização de radares navais e aéreos com capacidade de detectar consistentemente mísseis “sea skimming”, e também com uma ampla variedade de sistemas antimísseis automáticos capazes de fazer frente a mísseis antinavios supersônicos e ataques de saturação, os projetistas de mísseis antinavios tiveram que evoluir.

Essa evolução está se materializando na adoção do conceito “stealth”. Desde a introdução do caça F-117 na década de 80 do século passado que há por parte dos estrategistas e dos engenheiros um “movimento” no sentido de reduzir substancialmente a possibilidade de detecção de um “alvo”, suprimindo ou alterando algumas de suas características.

Se algo não pode ser detectado não poderá ser destruído.

A tecnologia “stealth” visa reduzir a “assinatura” de uma aeronave, navio ou míssil em todo o espectro eletromagnético.

Um míssil antinavio pequeno como o Harpoon (550 kg) tem um RCS em torno de 0,1 m2, muito grande se for comparado com o bombardeiro B-2 (150 toneladas) que é de 0,0014 m2.

Técnicas de forma e materiais que absorvam as ondas de radar se fazem necessários.

Uma redução substancial da assinatura térmica obriga que o míssil seja subsônico e de preferência, voe alto.

Também é interessante que o míssil use uma cabeça de busca por homing passivo, como por exemplo, um “sistema de imagem térmica”, já que as emissões na faixa de microondas de um radar ativo podem ser detectadas por um navio alvo, alertando a defesa.

Mísseis como o SLAM-ER ou o NSM adotam o conceito “stealth” em sua plenitude.

Míssil “stealth” SLAM-ER.

A bomba planadora JSOW C-1 com função antinavio também é outro exemplo do conceito stealth. Guiada por um sistema de imagem térmica (passivo), não é dotado de propulsão, alcançando 100 km quando lançada de uma aeronave em grande altitude.

Uma vantagem associada ao conceito stealth é a possibilidade de poder voar alto, não necessitando usar o perfil “sea skimming”. Na verdade, como dito anteriormente, não é desejável voar baixo.

Voar alto traz ainda outra grande vantagem, há um menor arrasto e, portanto, um incremento no alcance. O SLAM-ER só por ser Stealth tem o dobro do alcance do Harpoon, que lhe deu origem.

A compatibilização da tecnologia stealth com a velocidade supersônica não é de todo impossível, muitos alegam tê-la, como exemplo o Brahmos (russo/indiano) e o XASM-3 (japonês).

Claro que embora possível, deve haver um comprometimento do nível de furtividade que foi considerado aceitável tendo em vista o ganho com a velocidade supersônica na redução do tempo de reação.

O míssil de dois estágios SS-N-27 ainda na “fase subsônica”.

Uma solução interessante e inovadora foi adotada pelos russos com seu míssil 3M-54E Klub (SS-N-27). Ele é um míssil de dois estágios, sendo o primeiro impulsionado por um motor turbofan usado na fase de cruzeiro, permitindo grande alcance em velocidade subsônica e mantendo a furtividade alta durante a maior parte da trajetória.

Tão logo o sistema de radar ativo do míssil detecta o navio alvo após ser acionado no ponto predeterminado (em torno de 15 km de distância), o segundo estágio se solta e acelera até Mach 3, impulsionado por um foguete sólido com baixa emissão de fumaça.

Tal conceito combina as vantagens dos sistemas altamente furtivos e manobráveis com a velocidade supersônica.

Um outro conceito muito interessante parece ser o uso de mísseis balísticos de médio alcance na função antinavio. Os chineses anunciaram que já possuem operacionais mísseis ASBM (míssil balístico antinavio) com alcance de 3000 km e velocidade de Mach 10.

Pesando quase 15 t, o DF-21 é dotado de uma ogiva de reentrada com um sistema de orientação por radar ativo que é acionado na fase terminal da trajetória balística. Aletas móveis possibilitam que o veículo de reentrada mude sua trajetória de modo a atingir um navio com precisão.

Lançador do míssil balístico chinês DF-21

Míssil balístico chinês DF-21

Contra “mísseis balísticos antinavios” os sistemas antimísseis atuais são completamente ineficazes. A única defesa possível é por meio de sistemas antibalísticos altamente avançados, usados por um reduzido grupo de nações.

Outra tecnologia que desponta é a dos mísseis de cruzeiro hipersônicos dotados de propulsão scramjet. Tais mísseis poderão atingir velocidades acima de Mach 6 e com certeza os navios do futuro terão que lidar com esse tipo de ameaça também.

Um programa de alta prioridade no âmbito da U.S. Navy está sendo ansiosamente aguardado. Ele foi designado como LRASM (míssil antinavio de longo alcance) e visa selecionar o substituto do Harpoon naquela força.

Com certeza será interessante ver qual conceito irá melhor satisfazer as necessidades da mais poderosa marinha do mundo.

Mísseis Antinavios

13/06/2010

Autor: Bosco

Plano Brasil

Enquanto a visão de uma invasão de milhares de tanques aterrorizava a mente dos estrategistas ocidentais, a visão de centenas de navios capitaneados por porta-aviões gigantescos aterrorizava os estrategistas da ex-URSS.

Como diz um velho ditado, “a necessidade é a mãe da invenção”, e em relação à tecnologia militar não é diferente. Logicamente o “ocidente” se esmerou na luta antitanque e os soviéticos na luta antinavio.

Até a SGM o principal meio de atacar navios era o canhão, o torpedo e as bombas, respectivamente por navios, submarinos e aviões. Isso mudou a partir da década de sessenta com a introdução em larga escala pela URSS do míssil antinavio.

Já na época da SGM houve a introdução de armas guiadas lançadas por bombardeiros na tentativa de atingir navios, mas a tecnologia se mostrou tardia para influir no conflito de modo contundente, tornado-se madura só a partir da década de 60.

Foi só após o ataque ao destróier Eilat por mísseis Styx de fabricação russa lançados de lanchas egípcias na Guerra dos Seis Dias (1967) que o ocidente se deu conta, surpreso, que havia um imenso gap tecnológico com a URSS em relação à “mísseis de cruzeiro antinavios” (ASCM).

Os soviéticos estavam claramente na dianteira dessa corrida já que a OTAN, na mesma época, não possuía nenhum míssil antinavio dedicado.

Míssil Styx de origem russa.

Logo o “ocidente” arregaçou as mangas e se pôs a desenvolver seus “produtos”, e logo também, se viu a diferença da doutrina adotada pela URSS e pelo Ocidente, tendo em vista que os primeiros tinham como objetivo neutralizar uma armada sob a proteção de super porta-aviões.

Ou seja, para lograr êxito os mísseis soviéticos deveriam ter longo alcance, devido à cobertura aérea fornecida por um porta-aviões. Deveriam também ter uma ogiva excepcionalmente grande para poderem atingir de forma contundente um navio com mais de 60.000 toneladas de deslocamento e suas escoltas que em geral deslocavam mais de 10.000 t.

Tais requisitos operacionais fizeram com que os mísseis antinavios soviéticos assumissem um tamanho avantajado tendo em vista a conciliação da necessidade com a tecnologia disponível na época.

A Marinha Soviética, embora extremamente poderosa, se valia de seus submarinos para “projetar força” em detrimento dos navios de superfície, que tinham pouca expressão estratégica, e em geral não estavam sob o guarda chuva protetor de um porta-aviões. Tais características moldaram os mísseis ocidentais de modo a lhes conferir menores dimensões que seus congêneres do outro lado da Cortina de Ferro.

A ABORDAGEM SOVIÉTICA/RUSSA

Os soviéticos sempre deram ênfase a mísseis com poderosas ogivas e alcances que invariavelmente superam as 150 milhas náuticas.

Há uma variedade de opções que vão desde os subsônicos até os supersônicos, lançados por aeronaves, navios, submarinos e lançadores terrestres móveis.

Comparação do míssil russo SS-N-19 com um caça F-16.

Também, todos os sistemas de propulsão disponíveis foram utilizados, desde o foguete líquido, o foguete sólido, passando pelos turbopropulsores e motores ramjet.

Em geral são mísseis pesados e de grande alcance. Alguns chegam a 7 toneladas e alcançam 600 km.

Também são os únicos até agora a operarem mísseis antinavios supersônicos, como o AS-4 lançado pelo Backfire da década de 80 e os famosos SS-N-22 e SS-N-26, entre muitos outros. Só agora outros países os seguem, como a Índia, Taiwan e Japão.

Míssil russo SS-N-22

Enquanto a OTAN tinha no avião o vetor mais apropriado para ataques de grande alcance, os soviéticos, e depois os russos, tinham no poder de seus mísseis seu grande trunfo.

Para lograr êxito contra os grandes porta-aviões americanos os mísseis russos tinham que ter grande alcance e uma pesada ogiva que não raro chegava a 1 tonelada. A maioria dos mísseis tinha também uma versão dotada de ogiva nuclear.

Mísseis com grandes ogivas e grande alcance ficavam pesados e grandes, portanto, fáceis de serem detectado e interceptados.

Para tentar vencer as defesas de uma força tarefa capitaneado por um porta-aviões e sob o manto protetor do Sistema AEGIS a abordagem escolhida foi um incremento na velocidade, de modo a reduzir o tempo de reação da defesa.

Com esta foto podemos observar as dimensões dos lançadores de mísseis SS-N-12.

Míssil SS-N-12 Sandbox

Enquanto o Ocidente desenvolvia pequenos mísseis subsônicos com capacidade “sea skimming”, os soviéticos desenvolviam grandes mísseis supersônicos, alguns chegando a Mach 3, guiados por sistema inercial e com cabeça de busca autônoma baseada em um radar ativo, capacidade “fire-and-forget” e alcance OTH (além do horizonte).

A combinação de mísseis de grandes dimensões e velocidade supersônica trouxe alguns inconvenientes como, por exemplo, uma maior assinatura radar e térmica e uma menor capacidade de manobra.

Navio com lançadores de mísseis SS-N-12.

Outra característica da doutrina russa é o “ataque de saturação” que visa sobrecarregar as defesas do “grupo tarefa”.

Míssil supersônico russo SS-N-26

Do lado ocidental o míssil Tomahawk em sua versão antinavio (TASM) dos anos 80 foi o que mais se identificou com a doutrina soviética/russa. Tinha um alcance de 500 km e uma ogiva de 450 quilos.

Míssil Brahmos indiano baseado no SS-N-26 russo.

Ainda hoje o Tomahawk na sua versão Block IV é o míssil ocidental com capacidade antinavio de maior alcance, superando inclusive os grandes mísseis russos. Chega a 1000 milhas náuticas.

Mísseis soviéticos/russos (designação da OTAN):

• SS-N-1 Scrubber

• SS-N-2 Styx

• SS-N-3 Shaddock

• SS-N-7 Starbright

• SS-N-9 Siren

• SS-N-12 Sandbox

• SS-N-19 Shipwreck (P-700 Granit)

• SS-N-22 / AS-X-22 Sunburn (Moskit)

• SS-N-25 / AS-20 Switchblade (Harpoonski)

• SS-NX-26 Yakhont / Brahmos

• SS-N-27 (P-900 Klub)

• AS-1 Kennel

• AS-2 Kipper

• AS-4 Kitchen

• AS-5 Kelt

• AS-6 Kingfish

• AS-16 Kickback

• AS-17 Krypton

• AS-18 Kazoo

O CONCEITO OCIDENTAL

Já no lado ocidental, motivado pelo incidente do Eilat, e tendo em vista se contrapor à Marinha Soviética que em geral não estava sob a proteção de um porta-aviões, a tendência foi no sentido de desenvolver mísseis de menor tamanho, menor alcance e “pequenas” ogivas.

Dois mísseis se sobressaíram no Ocidente, o Exocet francês e o Harpoon americano. Esses dois exemplos resumem a doutrina ocidental em relação a mísseis anti-navios. Possuem capacidade OTH (além do horizonte), operam no modo LOAL (travamento após o lançamento), são subsônicos, de pequenas dimensões, pesando menos que 700 quilos, ogivas aptas a neutralizar navios de menor tonelagem (6000 t), guiados por um sistema inercial até um ponto pré-determinado onde ativam seu buscador autônomo baseado em um radar ativo miniaturizado e possuem perfil de vôo “sea skimming”, usando o “fundo” para enganar o radar e reduzir o tempo de reação da defesa.

O Exocet ficou famoso na Guerra das Malvinas nas mãos dos argentinos, conseguindo atingir algumas unidades britânicas. É um pequeno míssil subsônico, guiado por radar ativo, com motor foguete sólido e alcance em torno de 70 km. Pode ser lançado de navios, submarinos submersos, aviões de asa fixa, helicóptero de grande porte e plataformas costeiras.

O Harpoon tem o dobro do alcance e é propulsado por um turbojato miniaturizado. Também é subsônico, guiado por radar ativo, de peso leve, reduzida assinatura térmica e radar e grande capacidade de manobra, podendo inclusive efetuar manobras terminais tipo pop-up.

Míssil Harpoon americano.

Ao contrário dos grandes mísseis russos com ênfase anti porta-aviões, os mísseis antinavios ocidentais são compatíveis com caças de pequeno porte e alguns são disparados inclusive por tubos de torpedos convencionais de submarinos.

A capacidade OTH (além do horizonte) exige que o alvo seja designado por uma plataforma avançada, como por exemplo, um helicóptero ou um avião de patrulha marítima.

Mísseis antinavios subsônicos com alcance extremamente grande, por volta de 100 milhas náuticas, obriga a adoção de um sistema de data-link para que possam receber atualizações da posição do navio alvo em tempo real sob pena de não conseguirem detectá-lo nas coordenadas previstas.

Míssil russo SS-N-25

Vale salientar que mísseis com características ocidentais têm sido desenvolvidos e produzidos também na Rússia para armar navios de pequena tonelagem e aviões, sendo o SS-N-25 (Kh-35) um exemplo.

Mísseis “ocidentais”:

• Exocet

• Exocet Block 3

• Harpoon

• RBS15

• Otomat

• NSM

• Gabriel

• Penguin

• Maverick F

• SLAM-ER

• Kormoran

• Sea Eagle

• Tomahawk Block IV (?)

• “JSOW C-1 “

• XASM-3

MÍSSEIS DE PEQUENO PORTE LANÇADOS DE HELICÓPTEROS

O helicóptero é um meio imprescindível nas operações de guerra moderna. Nas operações navais não é diferente e ele desempenha as mais diversas funções que vão desde o resgate, esclarecimento, luta antisubmarina e guerra antisuperfície.

Míssil Sea Skua lançado de helicópteros.

Na função antisuperfície ele é um meio extremamente valioso tanto para esclarecimento e designação de alvos além do horizonte como no ataque direto a meios flutuantes com seus armamentos próprios.