Japan fears compromise on South Korea wartime labor could open Pandora's box of WWII issues

BY REIJI YOSHIDA

JUL 31, 2019

Foreign Minister Taro Kono was furious — or at least looked that way — during a July 19 face-off in Tokyo with South Korean Ambassador to Japan Nam Gwan-pyo.

Suddenly interrupting the Japanese-language translator for Nam, Kono began castigating the envoy for being “extremely rude” — a highly unusual scene for a high-level diplomatic meeting open to journalists and television crews from both countries.

“What the South Korean government is doing right now is tantamount to overturning the foundation of the post-World War II international order,” Kono thundered at Nam.

The ambassador had been speaking about Seoul’s earlier proposal to settle the wartime labor compensation issue by raising funds from both Japanese and South Korean companies, when Kono insisted that the enjoy was merely pretending he knew nothing about Japan’s earlier rebuttal of that proposal.

Tokyo has maintained a tough stance on the matter, with senior Japanese diplomats repeatedly emphasizing a single view; that South Korean President Moon Jae-in and his lieutenants have failed to grasp the meaning and magnitude of the wartime labor compensation issue for Japan.

Japan’s 1910-1945 colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula presents a number of emotional and thorny historical issues. So why does the wartime labor issue carry such importance for the Japanese government?

Officials in Tokyo say that the logic of a finalized ruling by South Korea’s Supreme Court last year ordering Japanese companies to pay redress is so radical that it could open a Pandora’s box.

For example, it could effectively nullify a landmark 1965 economic cooperation pact that was supposed to settle all compensation issues involving Japan’s colonial rule.

The ripple effects of that, Japanese diplomats say, could cascade into other issues, and even reignite World War II compensation issues with other countries.

On Monday, the Foreign Ministry held a briefing for reporters in Tokyo, distributing copies of records from normalization talks in the 1960s that they said showed the South Korean government had agreed that all wartime labor compensation issues were settled by the 1965 pact.

For Japanese officials, the way forward is clear.

“We can’t make any compromise. Even 1 millimeter,” a senior Foreign Ministry official recently said.

The ruling “totally runs against the idea behind Article 4 of the San Francisco treaty,” the official said, referring to the 1951 peace treaty inked by Tokyo and 48 countries to end the post-World War II occupation of Japan.

The San Francisco Peace Treaty obliged Japan to recognize the independence of Korea, while Article 4 of the pact stipulated that any property and claims between the two countries should be settled “through special arrangements” between the two parties. Based on this, Seoul and Tokyo launched post-colonial bilateral normalization talks in 1952.

After heated marathon negotiations, the two countries finally concluded in 1965 a basic relations treaty with an attached pact on economic cooperation.

Under the 1965 lump-sum pact, Japan agreed to extend a massive amount of “economic cooperation” to the South Korean government. The package consisted of grants worth $300 million and loans of $200 million over 10 years — funds totaling 1.6 times South Korea’s annual national budget at the time.

In return, the South Korean government agreed to use part of those funds to compensate individual South Korean wartime laborers forced to work in Japan.

South Korea’s president at the time, strongman Park Chung-hee, used most of the remaining funds for social and infrastructure development, a move that experts say helped the country to achieve rapid economic growth.

But the South Korean perspective on this shared understanding seemed to start to shift in 2005.

Under the administration of President Roh Moo-hyun, the South Korean government began arguing that the 1965 pact did not cover compensation issues for some of those who experienced war-related hardships, such as the “comfort women” — a euphemism used to refer to women who provided sex, including those who did so against their will, for Japanese troops before and during World War II.

At the time, Moon — who years later would run unsuccessfully for the presidency against Park Chung-hee’s daughter, before finally winning in 2017 — was Roh’s chief of staff.

Still, Seoul acknowledged in 2005 that the pact did cover the wartime labor issue, and that the South Korean government was responsible for paying compensation funds to individuals.

Then, last year, South Korea’s Supreme Court ruled that the 1965 pact was only designed to settle financial issues between the two countries, and that the rights of individuals to seek compensation was not terminated by the accord as it was predicated on Japan’s “illegal colonial rule.”

Based on that logic, the top court insisted in its ruling that Japanese firms pay damages for the “mental suffering” of four former wartime forced laborers.

The thinking behind the ruling came as a shock to Japanese officials, they said, because it bypassed the 1965 deal and created a new concept of “damages for mental suffering” from “inhuman acts” under what was described as Japan’s “illegal” colonial occupation.

In fact, Seoul has argued since the 1950s that Japan’s annexation of the Korean Peninsula was “illegal.” Tokyo has maintained that the annexation was done legally under international law at that time, and that many countries — including the United States and the U.K. — endorsed it.

So while last year’s Supreme Court ruling did not deny the effectiveness of the 1965 pact, it instead sought to circumvent it.

First, the ruling pointed out that the 1965 pact made no mention of the “illegality” of Japan’s colonial rule. Based on that point, the ruling then concluded that the lump-sum, government-to-government deal did not cover damages for the mental anguish of individual wartime laborers.

However, Japanese experts and officials point out that this could also mean that any South Korean individual who has experienced “mental suffering” under the “illegal” colonial rule may argue a case for compensation despite the 1965 pact.

“Japan’s colonial rule was not illegal. (South Korea) should observe what it agreed under the (1965) pact,” the senior Foreign Ministry official said.

The ruling “won’t have a positive impact on relations between European and African countries, either. No country has ever provided compensation for their colonial rule,” the official added.

In fact, while a number of African countries became independent in the 1950s and 60s, no Western country has ever paid out compensation for their colonial rule. Instead, many European countries extended economic assistance to their former colonies, just as Japan did under the 1965 deal with South Korea.

Another senior Japanese official said that if Tokyo accepted the ruling by South Korea’s Supreme Court, it could reignite wartime compensation issues with other Asian countries. The ruling “has created the right to claim a new category of damages” and if Japan accepted that argument, “it would mean nothing has been resolved as far as mental pain (under colonial rule) is concerned,” the official said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

At Monday’s Foreign Ministry briefing, copies of records created and kept by both the Japanese and South Korean sides documenting Tokyo-Seoul normalization talks held on May 10, 1961, quoted a South Korean representative as saying Seoul had demanded “appropriate compensation for mental and physical pain caused by forced recruitment.”

This may cast a different light on the central argument of the Supreme Court ruling, that “damages for mental suffering” of individuals due to “illegal” colonial rule were not covered by the 1965 government-to-government economic cooperation pact.

The records show that Seoul’s demands included compensation for both “mental and physical pain,” and that it was based on this argument that Japan concluded the 1965 pact to provide a massive amount of funds to its neighbor, Japanese officials said.

Article 2 of the pact explicitly confirms that all post-colonial compensation issues “have been settled completely and finally,” and that “no contention shall be made” thereafter, Japanese officials pointed out during Monday’s briefing.

“Whatever the cause of the mental pain might be, all of these issues were settled with this pact,” a senior Foreign Ministry official argued during the briefing. “Otherwise, phrases like ‘completely and finally’ wouldn’t have been used.”

The Japanese officials also noted that the records of the 1961 normalization talks produced by South Korean officials showed that Japanese negotiators had proposed Tokyo providing funds directly to “individuals,” rather than the South Korean government, to ease “emotional” frustration and promote mutual understanding between the two countries.

But according to the records, it was South Korean negotiators that rejected that idea during the 1961 meeting, saying that the Seoul government should pay compensation money to individuals after receiving funds from the Japanese government in a lump-sum deal.

“We will deal with this as a domestic problem,” the records of the meeting show the South Korean representative as saying. “There are issues over the number of people and the amount of money (to be paid), but we, the government, will make payments” to individual forced laborers.

The South Korean government, meanwhile, has repeatedly argued that the Supreme Court ruling should be respected given the principle of separation of legislative, administrative and judicial authorities.

In response, Japanese officials point out that under international law, South Korea is obliged to observe the 1965 pact as a state. According to international law, issues involving the principle of separation of the three powers should be dealt with domestically, Japan’s officials have said, urging the South Korean government to take measures to compensate for damages incurred to Japanese firms — some of which have seen their assets seized by the plaintiffs — based on the Supreme Court ruling.

Despite Japan’s initial approach to the row, which focused on the legal arguments, the situation between the two countries may now be one driven more by emotion rather than any discussion based on the specifics of talks in the 1960s.

In the nine months since the South Korean Supreme Court’s ruling last October, Seoul has yet to take any action despite repeated requests from the Japanese government.

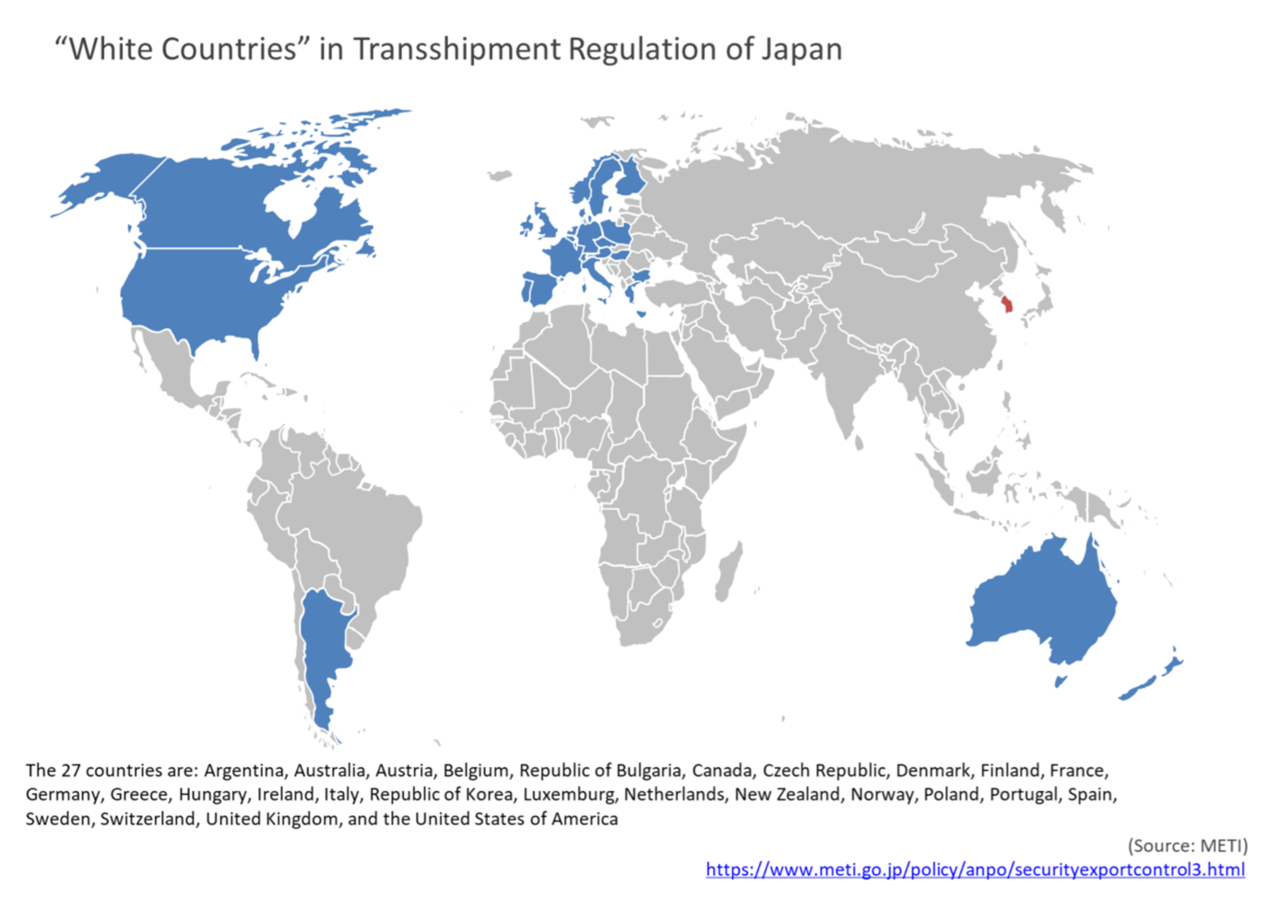

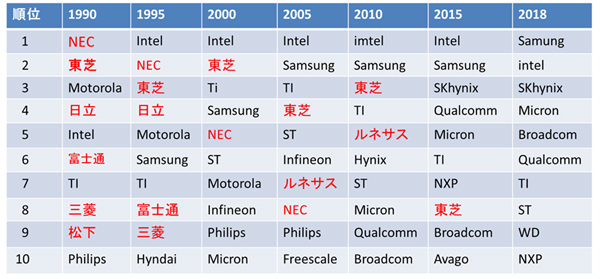

Then, on July 1, Tokyo announced the introduction of new export regulations on South Korea, including those on key materials desperately needed by South Korean firms to produce semiconductors and other high-tech devices.

Japanese officials have strongly denied the move was in retaliation for Seoul’s inaction on the wartime labor issue, but South Korean officials have criticized the new export regulations as a violation of free trade rules under the World Trade Organization.

The dispute has also led to a large-scale boycott of Japanese products in South Korea, as well as the cancellation of a number of cultural exchange events between the two countries.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2019/ ... UKtpuhMSUk

8:15 do video o Kono ficou bravo e nem deichou o lado coreano terminar de falar, ele disse que o governo da CS esta infligindo tratados internacionais por tanto não admite nenhuma exigencia da CS.