Russian Space Program Needs To Change

Moderador: Conselho de Moderação

Russian Space Program Needs To Change

Russian Space Program Needs To Change

The Kliper was never meant to be a lunar vehicle and was looked to as a replacement for the ageing Soyuz spacecraft in near-Earth orbits. Now it appears that everyone has forgotten the Kliper, instead suggesting the Soyuz as a lunar vehicle. The latter will almost certainly be the only link with the International Space Station (ISS) after the Americans finally ground their shuttles in 2010.

by Andrei Kislyakov

Moscow (RIA Novosti) Aug 12, 2007

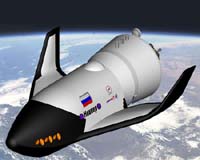

If the past is any guide, we will learn about the latest plans for the Russian space program at the end of August. On the 21st, the MAKS-2007 international aerospace show will open in Zhukovsky, outside Moscow. Why such certainty that important announcements will be made? Two years ago, at the previous show, visitors admired a mock-up of Russia's Kliper reusable spacecraft developed by Energiya, the flagship corporation of the Russian aerospace industry.

The Russian Space Agency (Roskosmos) announced that the craft would open up a new chapter in space exploration.

A year later, in Farnborough, the Space Agency declared that the Kliper project was as good as complete and announced a marathon program to upgrade the Soyuz craft, which has been around for 50 years. In between the shows, some attempts were made to reconcile the conflicting plans concerning manned flights to the Moon and Mars, but the situation was not made any clearer.

Now seems to be the time for a showdown, especially since the agency's head Anatoly Perminov will have an excellent opportunity to explain a lot of things as a professional.

One is, what kind of space program does Russia have? Six months ago, no one questioned that it did indeed have one. There was the Federal Space Program for 2006-2015. Later the Space Agency began talking about prospects for the period until 2040.

Now another question arises: if these are just sketches of plans that do not call for any great human effort or financing, that is one thing. If specific research and development are meant, not to mention experimental-design work, that is another. In that case, one will have to hark back to the remote 1930s and 1940s to shed light on the current strained developments.

But that is not all. Very recently, in early August, Space Agency deputy head Vitaly Davydov said that according to the program, no Moon expeditions were planned until 2015. The Space Agency has given a sober assessment of its possibilities for the period concerned, limiting the lunar program to three research satellites.

But Davydov developed his thought further, saying that the federal program would be updated. "In two years' time, in about 2010, we will extend it to 2020." This seems to me like a third program, in addition to the ones until 2015 and 2040 mentioned above, with all the financial and economic consequences that entails.

I may be wrong, and I am willing to listen to anyone who has a different interpretation, but that's how I see it. According to Davydov, work to update the existing space program is already under way and provides specifically for plans "which include not only manned flights to the Moon, but also beyond."

"Beyond" clearly points to Mars. But nothing is certain about the Moon. If the program covers the period until 2020, and we know that no lunar initiatives of note are planned before 2015, then the strategic offensive on our natural satellite must be prepared and effected in a space of five or so years. I might be willing to believe that could happen, but something is preventing me.

According to Vitaly Lopota, the newly elected Energiya president, the corporation has no money for the Moon program. He thinks, however, that funding will become available if the agency approves an appropriate program. This is a faint hope. But if such a program should see the light of day, how can it be smoothly incorporated into the plans that are already funded?

Today, no one can be sure what technology will be needed to tackle the Moon. A new space transport vehicle for Russia is already so urgent a matter that the issue has ceased to be a narrow engineering problem, rising before the Russian aerospace industry in all its magnitude.

This situation borders on the absurd. According to Alexei Krasnov, head of manned flights at the agency, who spoke on the issue in early August, it appears that the Federal Space Agency is rethinking the Kliper because it does not suit the Moon flights program. This is some news. Incidentally, Nikolai Sevastyanov, the former head of Energiya, who was put out to grass on July 31, was blamed for the pro-lunar slant of the corporation's plans.

The Kliper was never meant to be a lunar vehicle and was looked to as a replacement for the ageing Soyuz spacecraft in near-Earth orbits. Now it appears that everyone has forgotten the Kliper, instead suggesting the Soyuz as a lunar vehicle. The latter will almost certainly be the only link with the International Space Station (ISS) after the Americans finally ground their shuttles in 2010. Even if Russia's aerospace industry only manages to formulate a general strategy for developing future rocket technology, that would be a stroke of luck.

For the time being, the "un-Americanized" international station can only count on equipment developed 50 years ago, and possibly on the upcoming MAKS-2007 show. This is its only other chance.

The Kliper was never meant to be a lunar vehicle and was looked to as a replacement for the ageing Soyuz spacecraft in near-Earth orbits. Now it appears that everyone has forgotten the Kliper, instead suggesting the Soyuz as a lunar vehicle. The latter will almost certainly be the only link with the International Space Station (ISS) after the Americans finally ground their shuttles in 2010.

by Andrei Kislyakov

Moscow (RIA Novosti) Aug 12, 2007

If the past is any guide, we will learn about the latest plans for the Russian space program at the end of August. On the 21st, the MAKS-2007 international aerospace show will open in Zhukovsky, outside Moscow. Why such certainty that important announcements will be made? Two years ago, at the previous show, visitors admired a mock-up of Russia's Kliper reusable spacecraft developed by Energiya, the flagship corporation of the Russian aerospace industry.

The Russian Space Agency (Roskosmos) announced that the craft would open up a new chapter in space exploration.

A year later, in Farnborough, the Space Agency declared that the Kliper project was as good as complete and announced a marathon program to upgrade the Soyuz craft, which has been around for 50 years. In between the shows, some attempts were made to reconcile the conflicting plans concerning manned flights to the Moon and Mars, but the situation was not made any clearer.

Now seems to be the time for a showdown, especially since the agency's head Anatoly Perminov will have an excellent opportunity to explain a lot of things as a professional.

One is, what kind of space program does Russia have? Six months ago, no one questioned that it did indeed have one. There was the Federal Space Program for 2006-2015. Later the Space Agency began talking about prospects for the period until 2040.

Now another question arises: if these are just sketches of plans that do not call for any great human effort or financing, that is one thing. If specific research and development are meant, not to mention experimental-design work, that is another. In that case, one will have to hark back to the remote 1930s and 1940s to shed light on the current strained developments.

But that is not all. Very recently, in early August, Space Agency deputy head Vitaly Davydov said that according to the program, no Moon expeditions were planned until 2015. The Space Agency has given a sober assessment of its possibilities for the period concerned, limiting the lunar program to three research satellites.

But Davydov developed his thought further, saying that the federal program would be updated. "In two years' time, in about 2010, we will extend it to 2020." This seems to me like a third program, in addition to the ones until 2015 and 2040 mentioned above, with all the financial and economic consequences that entails.

I may be wrong, and I am willing to listen to anyone who has a different interpretation, but that's how I see it. According to Davydov, work to update the existing space program is already under way and provides specifically for plans "which include not only manned flights to the Moon, but also beyond."

"Beyond" clearly points to Mars. But nothing is certain about the Moon. If the program covers the period until 2020, and we know that no lunar initiatives of note are planned before 2015, then the strategic offensive on our natural satellite must be prepared and effected in a space of five or so years. I might be willing to believe that could happen, but something is preventing me.

According to Vitaly Lopota, the newly elected Energiya president, the corporation has no money for the Moon program. He thinks, however, that funding will become available if the agency approves an appropriate program. This is a faint hope. But if such a program should see the light of day, how can it be smoothly incorporated into the plans that are already funded?

Today, no one can be sure what technology will be needed to tackle the Moon. A new space transport vehicle for Russia is already so urgent a matter that the issue has ceased to be a narrow engineering problem, rising before the Russian aerospace industry in all its magnitude.

This situation borders on the absurd. According to Alexei Krasnov, head of manned flights at the agency, who spoke on the issue in early August, it appears that the Federal Space Agency is rethinking the Kliper because it does not suit the Moon flights program. This is some news. Incidentally, Nikolai Sevastyanov, the former head of Energiya, who was put out to grass on July 31, was blamed for the pro-lunar slant of the corporation's plans.

The Kliper was never meant to be a lunar vehicle and was looked to as a replacement for the ageing Soyuz spacecraft in near-Earth orbits. Now it appears that everyone has forgotten the Kliper, instead suggesting the Soyuz as a lunar vehicle. The latter will almost certainly be the only link with the International Space Station (ISS) after the Americans finally ground their shuttles in 2010. Even if Russia's aerospace industry only manages to formulate a general strategy for developing future rocket technology, that would be a stroke of luck.

For the time being, the "un-Americanized" international station can only count on equipment developed 50 years ago, and possibly on the upcoming MAKS-2007 show. This is its only other chance.

- cabeça de martelo

- Sênior

- Mensagens: 39476

- Registrado em: Sex Out 21, 2005 10:45 am

- Localização: Portugal

- Agradeceu: 1137 vezes

- Agradeceram: 2847 vezes

gral escreveu:Hmm, pelo menos um dos projetos de expedição à Lua dos russos nos anos 60 era baseado numa versão da Soyuz. Vale a pena investir na Soyuz ou será que o projeto já deu o que tinha que dar?

Ola Gral

Depende do que se espera do projeto.

A Soyuz sempre foi pensada como a forma mais leve e barata de se transportar 3 pessoas ate o espaço e depois retornar a Terra.

Uma Soyuz completa pesa cerca de 7400Kg, seu modulo de retorno pesa cerca de 3000Kg.

Uma Apolo, que também transporta o mesmo numero de tripulantes, em uma missão parecida em órbita terrestre, pesa pelo menos o dobro disto, o modulo retorno pesa cerca de 5800Kg.

A Soyuz foi pensada para “caber” no lançador R-7, principal foguete soviético / russo. Este lançador tem uma carteira de lançamento de cerca de 1700 lançamentos, para que tenham uma referencia todos os foguetes americanos somados não tem mais de 1400 lançamentos.

Com um foguete mais simples, produzido em larga escala e já provado, os custos de lançamento da Soyuz bem como a sua segurança atinge níveis acima dos outros programas tripulados.

Esta é a grande virtude da Soyuz. Obviamente ela tem defeitos.

Nenhuma nave com relação de massa por assentos tão baixa sofreria limitações operacionais.

A principal delas é o numero de assentos limitados a 3.

A Apolo, apesar de não se usar operacionalmente esta capacidade, pode se levar até 4 pessoas em uma configuração densa.

No Space Shuttle pode se levar 7 pessoas em vôo normal e até 10 em configuração densa.

No Orion, futura nave tripulada da NASA tem capacidade para 6 pessoas

O Kliper, futura nave tripulada Russa tem capacidade para 6 pessoas, 7 em configuração densa.

A resposta final seria.

Qual a utilização que se quer dar a nave?

Se a resposta for, voar com ate 3 pessoas para uma órbita terrestre em custo baixo, a Soyuz é imbatível.

Se a necessidade for, voar com mais de 3 pessoas, ai são necessárias outras opções, invariavelmente mais caras.

Elizabeth

Ainda sobre este tema, uma resposta minha em outro forum.

Ola Fabio, sobre a sua pergunta.

Pq gastar esforços para ir a Lua?

Este assunto é longo e delicioso. Pra encurtar em muito a historia, o resumo é o seguinte.

A manutenção de um programa eminentemente orbital, como a ISS amplificaria um questionamento que a NASa sobre hoje, que é, porque motivo os custos do programa ISS cresceram tanto durante o programa e os resultados científicos não são nada espetaculares se comparados aos do programa MIR, bem menos pomposo que a ISS.

Existiam duas alternativas.

Voltar a Lua

Ir a Marte

A segunda alternativa exigiria uma profunda reformulação na NASA de hoje que é completamente diferente daquela dos anos de 1960 durante o programa Apolo. Esta reformulação mexeria com os quadros funcionais, com as relações com fornecedores, aumentaria os riscos políticos e tecnológicos.

Isto é tudo que a NASA de hoje não quer. Mudança.

Ir a Lua por sua vez, é possível manter estruturas mais próximas a atual, diminuir os riscos e necessidade de eficiência associados a empreitada. Boa parte dos hardwares necessários são variações dos atuais existentes no programa Space Shuttle ou são re-leituras do programa Apolo.

Sem um inimigo a ser batido como nos anos de guerra fria, com déficits a serem considerados no orçamento, com uma estrutura menos eficiente do que nos anos de ouro da NASA, ir a Lua é um meio termo entre a cultura paquidérmica do atual programa e o desafio de ir a Marte.

Quanto ao artigo: Russian Space Program Needs To Change

Eu não posso falar muito sobre isto, mas no texto o autor referencia muito o programa Russo com o programa Americano da próxima década, dentro de uma referencia direta, sim parece lógico que o programa russo precisa de mudança, mas existe uma outra óptica que é o fato que a Rússia não deve necessariamente seguir a NASA nos seus planos futuros.

Por uma serie de motivos. Um deles é que não tem saúde financeira para tal, outro é que ir a Lua para o programa russo, mesmo que financeiramente possível por hipótese pode representar um desvio de foco do que efetivamente os russos devem fazer no espaço daqui a uma década.

O que vai ser do programa russo daqui a uma década, infelizmente não posso falar, mas asseguro que em nada tem haver com a tese do autor deste texto.

Existem duas correntes dentro das políticas espaciais russas. Uma delas é a pragmática, na qual defende um programa mais enxuto em focos de atenção e com resultados mais mensuráveis.

Uma segunda corrente defende um programa de espectro mais amplo, englobando mais vertentes associadas a industria espacial. Este artigo esta alinhado com esta segunda corrente que hoje não é efetivamente quem manda na Roskosmos.

Todo gestor de programa espacial russo hoje pertence a uma corrente, as coisas são bem polarizadas por aqui, e os debates sejam eles em reuniões, comitês de planejamento, conversas de corretor ou mesmo na mesa do bar no happy hour costumam ser bastante agitadas.

Elizabeth

Ola Fabio, sobre a sua pergunta.

Pq gastar esforços para ir a Lua?

Este assunto é longo e delicioso. Pra encurtar em muito a historia, o resumo é o seguinte.

A manutenção de um programa eminentemente orbital, como a ISS amplificaria um questionamento que a NASa sobre hoje, que é, porque motivo os custos do programa ISS cresceram tanto durante o programa e os resultados científicos não são nada espetaculares se comparados aos do programa MIR, bem menos pomposo que a ISS.

Existiam duas alternativas.

Voltar a Lua

Ir a Marte

A segunda alternativa exigiria uma profunda reformulação na NASA de hoje que é completamente diferente daquela dos anos de 1960 durante o programa Apolo. Esta reformulação mexeria com os quadros funcionais, com as relações com fornecedores, aumentaria os riscos políticos e tecnológicos.

Isto é tudo que a NASA de hoje não quer. Mudança.

Ir a Lua por sua vez, é possível manter estruturas mais próximas a atual, diminuir os riscos e necessidade de eficiência associados a empreitada. Boa parte dos hardwares necessários são variações dos atuais existentes no programa Space Shuttle ou são re-leituras do programa Apolo.

Sem um inimigo a ser batido como nos anos de guerra fria, com déficits a serem considerados no orçamento, com uma estrutura menos eficiente do que nos anos de ouro da NASA, ir a Lua é um meio termo entre a cultura paquidérmica do atual programa e o desafio de ir a Marte.

Quanto ao artigo: Russian Space Program Needs To Change

Eu não posso falar muito sobre isto, mas no texto o autor referencia muito o programa Russo com o programa Americano da próxima década, dentro de uma referencia direta, sim parece lógico que o programa russo precisa de mudança, mas existe uma outra óptica que é o fato que a Rússia não deve necessariamente seguir a NASA nos seus planos futuros.

Por uma serie de motivos. Um deles é que não tem saúde financeira para tal, outro é que ir a Lua para o programa russo, mesmo que financeiramente possível por hipótese pode representar um desvio de foco do que efetivamente os russos devem fazer no espaço daqui a uma década.

O que vai ser do programa russo daqui a uma década, infelizmente não posso falar, mas asseguro que em nada tem haver com a tese do autor deste texto.

Existem duas correntes dentro das políticas espaciais russas. Uma delas é a pragmática, na qual defende um programa mais enxuto em focos de atenção e com resultados mais mensuráveis.

Uma segunda corrente defende um programa de espectro mais amplo, englobando mais vertentes associadas a industria espacial. Este artigo esta alinhado com esta segunda corrente que hoje não é efetivamente quem manda na Roskosmos.

Todo gestor de programa espacial russo hoje pertence a uma corrente, as coisas são bem polarizadas por aqui, e os debates sejam eles em reuniões, comitês de planejamento, conversas de corretor ou mesmo na mesa do bar no happy hour costumam ser bastante agitadas.

Elizabeth

- LeandroGCard

- Sênior

- Mensagens: 8754

- Registrado em: Qui Ago 03, 2006 9:50 am

- Localização: S.B. do Campo

- Agradeceu: 69 vezes

- Agradeceram: 812 vezes

LeandroGCard escreveu:Koslova escreveu:

Nenhuma nave com relação de massa por assentos tão baixa sofreria limitações operacionais.

Elizabeth

Desculpe Koslova, mas acho que você quis dizer "...deixaria de sofrer limitações operacionais".

Se não for isto eu não entendi.

Leandro G. Card

Ola Leandro

A frase esta escrita errada, tenho a mania de não ler o texto que escrevo antes de enviá-lo.

Onde escrevi:

“Nenhuma nave com relação de massa por assentos tão baixa sofreria limitações operacionais.”

Leia

“Nenhuma nave com relação de massa por assentos tão baixa deixaria de sofrer limitações operacionais”

Em outros termos, a capacidade reduzida de tripulantes é o preço que o projeto da Soyuz paga para manter a massa abaixo de 7500Kg, capacidade do lançador R-7.